Best challenge I’ve seen in the course so far. (I might be a little biased)

Anyways, attached to the challenge is nothing but a few lines of Python:

from Crypto.Util.number import bytes_to_long, long_to_bytes, getPrime

import base64

from secret import flag, key

def cipher(k, m, n):

return (k * m) % n

def xor(k, m):

return bytes(a ^ b for a, b in zip(m, k))

def main():

k, m = bytes_to_long(key), bytes_to_long(flag)

n = getPrime(1024)

assert m < n and len(flag) == len(key)

c1 = long_to_bytes(cipher(k, m, n))

c2 = xor(key, flag)

print("c1 =", base64.b64encode(c1).decode())

print("c2 =", base64.b64encode(c2).decode())

print("n =", n)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()and an output of the script:

c1 = Lrh/EMfrRXqShQQqw+Zd/w6Nn2MwaWT5s0Xvb6AAq+NE4FxIvvPSuzLJbv9VwcJv0F1LlOfnfvc3j/eFM5BWpTujw6dQ8ZtjV6dOqqnLPC1lKdDZEmt5XaINbKe4CIIT37V1qtR2jqy7K1xjCUJJyGkrgFI9vXWyfrQAHo2JSt4=

c2 = ////////+/33/////////////////v////////////////9///////f/////////////3//f////////////////

n = 150095186069281777851468726257751810997446691788728681013850021750670480757667073571298768531705071802820728411143863036993470518226749117889851508979626068982736226357060650073869307154521010066655609905126167748092779979732912821644834005606143609309269768565568485061354218686729973438920060109916387047693The goal, obviously, is to decrypt the message from c1,

c2 and then obtain the flag.

The encryption algorithm implemented by the script (which is very simple) could be summarized as:

\[ \begin{align} c_1 & \equiv km \mod n \\ c_2 & = k \oplus m \end{align} \]

where \(k\) is the key, \(m\) the message (with the flag), \(n\) a large prime number and \(\oplus\) the bitwise XOR operator. Looks

like we just have to solve the system of equations. Note that \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are integer versions of

c1 and c2, which are base64-encoded.

Looks like we just had to solve the system of equations…

Not so easy!

We’ll first try to use the method of substitution. Since \(k = c_2 \oplus f\) (XOR is self-inverse), from (1), we get

\[ c_1 \equiv m(c_2 \oplus m) \mod n \]

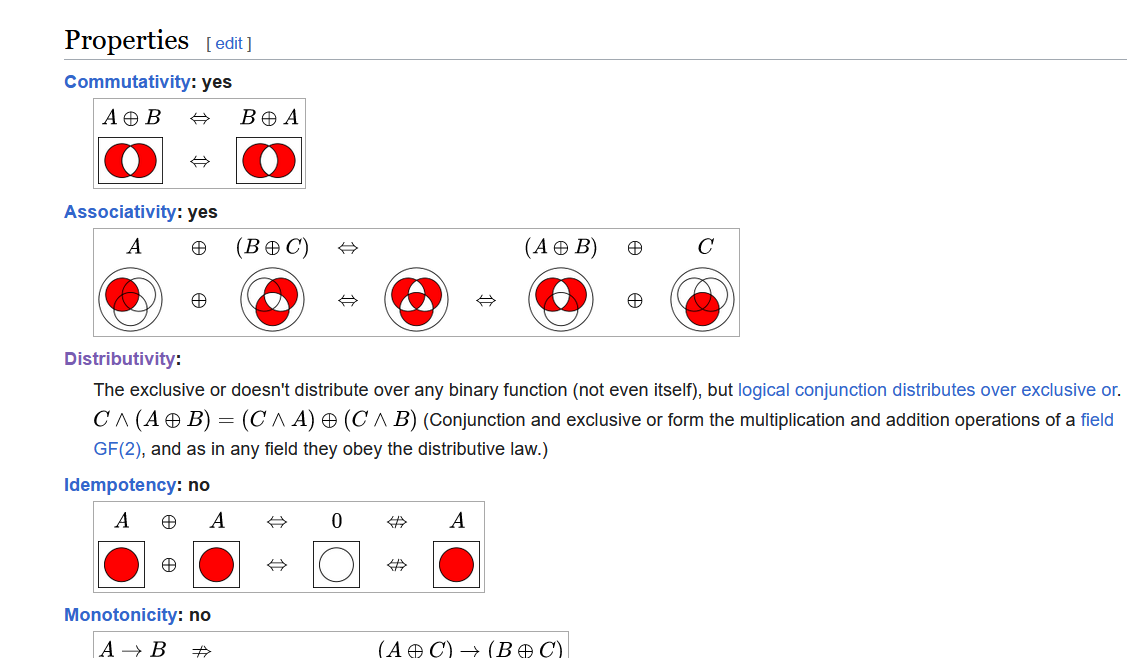

Wait. Multiplying by an XOR? Is there any nice property to simplify this?

No useful information. What would WolframAlpha tell us about it?

We’re doomed. We can’t do something like \(m^{-1}c_1 \equiv c_2 \oplus m\) either, since \(m\) would appear on both sides which makes things worse. If that funny looking circle with a cross was just a \(+\), we would’ve solved it in seconds. (definitely not foreshadowing)

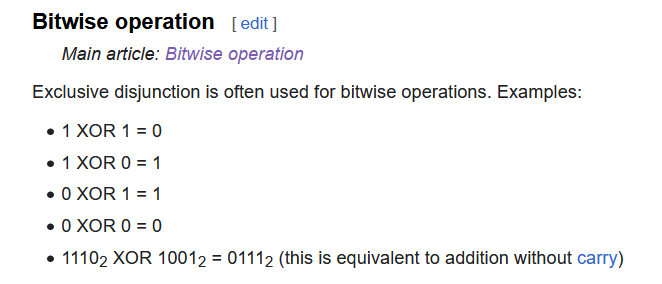

Bitwise operations are arithmetic (change my mind)

Wait what? Looks kinda sus.

To see how they relate, let’s try to add the two binary numbers:

1110

+ 1001

_1____

10111What if we removed the carry?

1110 1110

+ 1001 (which is just) XOR 1001

______ ________

0111 0111This fact can be verified by noting the only case where \(+\) and \(\oplus\) (on two bits) differ, is when both operands are \(1\).

Since the two results look incredibly similar, it might be possible to “guess” the sum by just looking at the XOR.

???? ????

+ ???? XOR ????

______ ________

???? 0111In the above case, the XOR result has three \(1\)’s (which can only be a result of \(1 \oplus 0\) or \(0 \oplus1\) ), we infer that the last 3 bits of the operands, when summed, are all \(1\)’s without a carry. A possible configuration could be:

?001 ?001

+ ?110 XOR ?110

______ ________

?111 0111(Note that the sum stays constant no matter which configuration is chosen.)

For the first bit, though, things might get trickier. \(0 \oplus 0\) and \(1 \oplus 1\) both result in \(0\). As for the sum, we could either have \(0 + 0\) with no carry, or \(1 + 1\), with a carry to the left. If there is a carry bit, it would add \(2^{4} = 16\) to the sum itself.

0001 0001

+ 0110 XOR 0110

______ (first case) ________

0111 0111 1001 1001

+ 1110 XOR 1110

_1____ (second case) ________

10111 0111That also means, given a fixed XOR result, whenever it has a \(0\) in the \(i\)th position [1], the amount of possible sums doubles. If we put a \(0\) in our guessed sum at that position, the actual sum could either be exact or differ by \(2^{i+1}\) the value of that carry bit.

Luckily, if you look carefully, c2 just looks like a

bunch of slashes (11111 in base64), which means most of the

bits are just gonna be 1 with a few exceptions.

Let’s turn c2 into a binary string:

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111011 11111101

11110111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111110 11111111 11111111

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

11111111 11111111 11111111 01111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

11110111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

11111111 11111111 11111111 11011111 11111111 11011111 11111111 11111111

11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111 11111111

11111111 11111111We can see there are 8 0’s, and the sum \(k+m\) could take only \(2^8 = 256\) possible values.

To find out all candidate values for the sum, we select \(k \oplus m\) as our first candidate. For

each 0 bit at the \(i\)th

position from the right, a new set of candidate values could be

generated by adding \(2^{i+1}\) to the

existing set.

# get positions of all 0 bits in c2

bin_c2 = bin(c2)[2:]

zero_positions = [i for i, b in enumerate(bin_c2[::-1]) if b == '0']

print(zero_positions) # [101, 117, 203, 247, 352, 459, 465, 474]

# enumerate all possible k + m values

possible_sums = [c2]

for i in zero_positions:

possible_sums += [s + 2 ** (i+1) for s in possible_sums]

print(len(set(possible_sums))) # 256[1] The position of LSB is 0 in this context

Time for some high school algebra!

To simplify the rest of the solution, let’s just assume we already have \(k +m\), and we call it \(s\). (I do not know how to name things) From (2), we get:

\[ c_1 \equiv m(s - m) \mod n \]

Now we call finally simplify things for a bit.

\[ -m^2 + sm - c_1 \equiv 0\mod n \\ -4m^2 + 4sm - 4c_1 \equiv 0\mod n \\ -(2m-s)^2+s^2-4c_1 \equiv 0 \mod n \\ (2m-s)^2 \equiv s^2-4c_1 \mod n \]

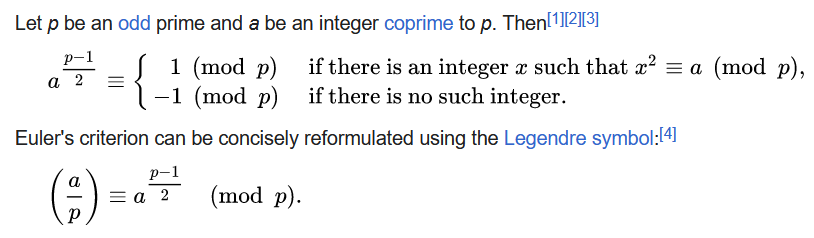

In case you failed high school math, I used a technique called completing the square, in order to obtain the \(x^2 \equiv a \mod n\) relation with only \(x\) unknown. The reason I multiplied the whole equation by \(4\), is to eliminate any fraction appearing after completing the square, as both sides of the modular equivalence must be integers.

Hold on, a modular quadratic equation? I need to google harder for this

If we have the correct \(s\), the solution must exist. The above could be useful for invalidating candidate values of \(s\).

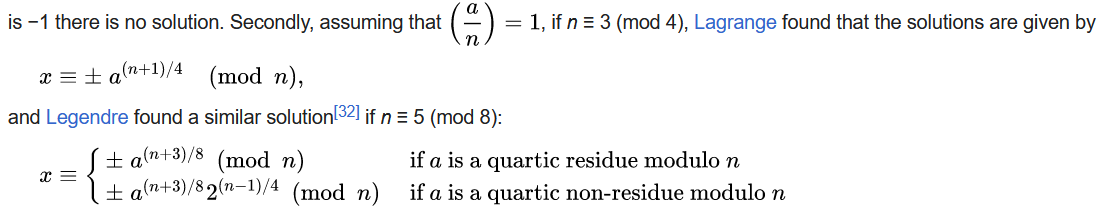

Looks like we can actually solve for \(x\) if \(n\) takes specific values. Let’s check…

>>> print(n % 8)

5Now that we have four possible solutions for \(x\), we can just calculate \(m \equiv \dfrac{s + x}{2} \mod n\) and check if any of the encoded versions of \(m\) contains the flag.

Brute force… the smart way

In reality, we don’t actually have the exact \(s\), but possible values of \(s\). We’ll use the ultimate CTF technique — test if each candidate for \(s\) enables us to solve for \(m\) that contains the flag. Since we only have \(2^{8}\) candidates, this algorithm can actually find the solution in a matter of seconds. That already works way better than just brute-forcing for \(k\) naively (which is one of the \(2^{256}\) possible values).

In other words: mafs good.

Solution script

from base64 import b64decode

c1 = 'Lrh/EMfrRXqShQQqw+Zd/w6Nn2MwaWT5s0Xvb6AAq+NE4FxIvvPSuzLJbv9VwcJv0F1LlOfnfvc3j/eFM5BWpTujw6dQ8ZtjV6dOqqnLPC1lKdDZEmt5XaINbKe4CIIT37V1qtR2jqy7K1xjCUJJyGkrgFI9vXWyfrQAHo2JSt4='

c2 = '////////+/33/////////////////v////////////////9///////f/////////////3//f////////////////'

n = 150095186069281777851468726257751810997446691788728681013850021750670480757667073571298768531705071802820728411143863036993470518226749117889851508979626068982736226357060650073869307154521010066655609905126167748092779979732912821644834005606143609309269768565568485061354218686729973438920060109916387047693

def xor(k, m):

return bytes(a ^ b for a, b in zip(m, k))

def int_to_bytes(x: int) -> bytes:

return x.to_bytes((x.bit_length() + 7) // 8, 'big')

# decode from base64 to int

c1 = int.from_bytes(b64decode(c1))

c2 = int.from_bytes(b64decode(c2))

bin_c2 = bin(c2)[2:]

zero_positions = [i for i, b in enumerate(bin_c2[::-1]) if b == '0']

possible_sums = [c2]

for i in zero_positions:

possible_sums += [s + 2 ** (i+1) for s in possible_sums]

for s in possible_sums:

a = s ** 2 - 4 * c1

assert a > n

a = a % n

# test if a is quadratic residue mod n

if pow(a, (n - 1) // 2, n) == 1:

# since n = 5 mod 8, we can have one of the following solutions

# depending on if a is a quintic residue mod n

x1 = pow(a, (n + 3) // 8, n) * pow(2, (n - 1) // 4, n) % n

x2 = pow(a, (n + 3) // 8, n)

# I have no idea how to check for quintic residues

if pow(x1, 2, n) == a:

x = x1

else:

x = x2

# check if x is a solution

assert pow(x, 2, n) == a

# m should be an integer

if (x + s) % 2 == 1:

continue

# account for the plus or minus x

possible_m = [(x + s) // 2 % n, (s - x) // 2 % n]

for m in possible_m:

assert (s - m) * m % n == c1

m = int_to_bytes(m)

if b'flag' in m:

print('flag: ', m)

print('key: ', key := xor(m, int_to_bytes(c2)))

assert int.from_bytes(m) * int.from_bytes(key) % n == c1

break